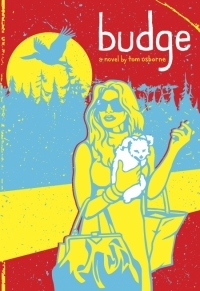

Budge

Budge is one of the more quirky, unconventional, picaresque novels to come along in a while. It can be pleasurable, if the reader is willing to roll with Osborne’s approach to prose, which is original, if not necessarily expedient. Osborne tends to dance all around a point before he makes it, and his paragraphs can go on for quite a bit, without necessarily being cumbersome. In comparison to similar authors, he’s like Faulkner without the density, Stein without the obtuseness, or Thomas Wolfe without the extravagance; of those, he’s closest to Wolfe. There’s a rhythm to Budge‘s text that Osborne might not have achieved with a more minimalist approach. There’s a sense he’s luxuriating in the weaving of his narrative, repeating certain key phrases, winking at the reader and leading him through a meandering, though focused plot. To fully appreciate Budge, we must relinquish our trust to Osborne, a somewhat loopy shaman.

Budge tells the story of Louella Debra Poule, a recovering drug addict who has been paroled from prison. The reader shares her odyssey as Debra moves into the condo of her expired, estranged mother, to sort through the wreckage of her past. She begins to establish a fresh network of friends, including Aunt Inga, Meagre Deerfield (a Native Indian) Mona Rose (a neighbor), and Alcina (a tall, black transvestite). Understandably, Louella fears backsliding or an unwanted visit from past gangster associates, such as Jimmy Flood (her ex-boyfriend) and Blacky Harbottle.

“Budge” refers to one’s effort to move in a different direction, when she finds she has lost her way. Once she has unwittingly stepped into the abyss, sometimes the most difficult step is the first, towards self-extrication. She doesn’t want to budge. Osborne is reassuringly inclusive in his reflection on salvation and the exorcism of self-loathing. Though the women (for the most part) fare better, he never suggests that any of the characters, however unsavory, are intrinsically corrupt or beyond redemption.

Tom Osborne warrants a great deal of praise for freshness of content, viewpoint, and plot. He knows how to use language with skill and verve. Though he takes such delight in describing his milieu, he sometimes verges on self-indulgence. It’s not always easy to process his extensive text at the outset, but persistence is rewarded.

There are numerous charming, subtly beguiling aspects to Osborne’s Budge. It’s impressive that he’s able to address some very serious topics (substance abuse, abandonment, drug trade) without glamorizing transgression or getting bogged down in gravitas. The author’s sense of humanity, proportion, and wit make for a memorable excursion.

Reviewed by

Christopher Soden

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.