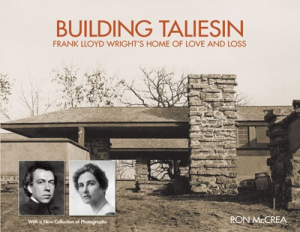

Building Taliesin

Frank Lloyd Wright's Home of Love and Loss

Ron McCrea’s Building Taliesin: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Home of Love and Loss covers the years from 1910 through 1914, the period during which the architect conceived and built his masterpiece in the hills of Wisconsin, accompanied by his mistress, Mamah Borthwick; that she was also murdered there, along with her two children and several visitors, was the love story’s horrifying end.

This comprehensive book is clearly a labor of love on the author’s part (he even includes a photograph of his wife and himself at the subjects’ hillside retreat above Florence, where the idea of Taliesin was born). The straightforward narrative reads like a detective’s notes, and in the accounting of each research discovery one senses the author’s delight.

A scrap-book-like format displays a wealth of fascinating information, especially in the form of a series of recently discovered photographs by draftsman Taylor Woolley depicting the house under construction. Evident in these warm black-and- white images is the aura of a most lovely dream realized as both a professional and personal accomplishment by Wright. Almost sketch-like in their appearance is another extraordinary set of panoramic photographs by Wright himself of the valleys characterizing the land he had known as a child and would develop to great acclaim.

However, also owing at least in part to the book’s format is an unfortunate sense of fragmentation that characterizes the entire effort. The reader is fairly assaulted with a barrage of reproduced documents, albeit usually handsomely displayed, from letters to illustrations to photographs, plus quotes from newspaper accounts—without a strong foundation on which to tack all this information. McCrea never provides the equivalent of an establishing shot, as it were.

The author’s introduction, where it would make sense to prime his canvas, never sufficiently describes the design significance of Taliesin and why his readers should care that it exists (now in its third incarnation) or what happened there. It’s the house, after all, that deserves to be the real subject here, and while McCrea may assume we know why it’s important, most readers won’t. The author also misses an opportunity to tell an amazing story, employing a good old beginning, middle, and end with all its inherent drama; instead he uses a workmanlike, reportage writing style to simply set up (and often repeat) his research findings.

McCrea does relate things to be treasured, foremost among them the wealth of strong, emancipated women functioning as indispensable satellites in Wright’s orbit. Borthwick, a translator who divorced her husband to be with Wright, is certainly to be counted among them, as is her mentor and employer, feminist Ellen Key. The professional support of Wright’s aunts, mother, and sister and the architectural legacies of his efforts for them is also celebrated, but without drawing much attention to its uniqueness. Perhaps most touching are a sketch and images of an extraordinary puppet theater Wright built for the son he abandoned, Llewellyn.

Building Taliesin: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Home of Love and Loss adds an important layer to the vast body of books about Wright, and for this it is to be valued. One only wishes the nuts-and-bolts story of this remarkable structure itself were fleshed out more fully here.

Reviewed by

Julie Eakin

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.