Canoodlers

The speaker in Bennett’s poetry questions her mother’s love and her sexuality, offering coming-of-age insight.

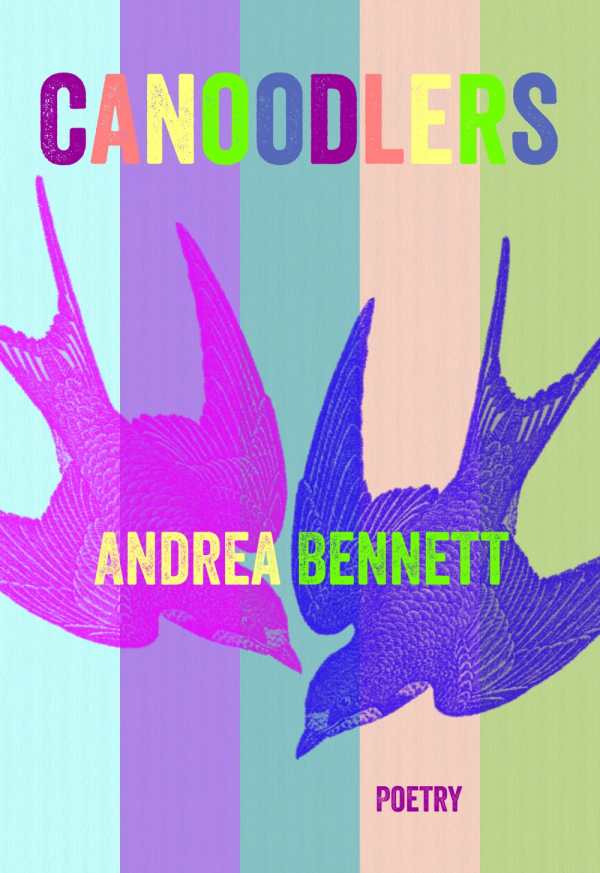

Canoodlers looks hip—bright colors, swooping birds, titles in the table of contents alternating between black and gray, all befitting the coming-of-age story told in the book. Related in prose poems, the speaker’s connections and disconnections start with her parents—a nature-loving, supportive father and an alcoholic, attractive mother. These poems have a disaffected tone as the speaker struggles to understand her mother’s antipathy and her own sexuality.

The book opens with a very short poem, “Epigraph,” which sets the stage for the speaker’s family life:

You have a poetic sensibility,

my father says. Maybe,

when you clean your room,

you will find it.

The speaker’s father is a little bit sly, but he’s also aware of his daughter’s predilections. Birds become a pervasive image set throughout a poem about the father taking the daughter birdwatching. The speaker observes her mother differently, as she watches her touch another man flirtatiously, watches the local pervert stare over the fence at her, or watches her drive home drunk. The mother’s decisions are questioned throughout the book, providing a constant thrum of insecurity as the speaker asks the age-old question, why doesn’t my mother love me?

Other poems reference pop culture, from Hitchcock films to commentaries on fame. As the book progresses, the speaker explores her sexuality, finding partners in both men and women. The book has moments of humor, “No one is shy at the Easter egg hunt,” juxtaposed with graver ones, “A twenty-sixer / of my father’s whiskey, / twelve and a half / little pills. // an ambulance, / the hospital.”

The prose poems formed here often feel anecdotal and lack the tension a more formal approach might have offered. Just as the young person at the center slouches through life, some of the poems seem to do the same. Still, the book has moments of rising above the coming-of-age theme into a state of empowerment, as in “My loyal cabal” where the speaker chooses her own power—“I’m not shooting arrows through hoops. Not about to turn into a tree. No. I am bending over and rubbing the hair on my shins. I am humming Kate Bush, getting ready for a run.”

These poems will have a strong appeal for teens and twenty-somethings, because they relay a story with which they are intimately acquainted.

Reviewed by

Camille-Yvette Welsch

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.