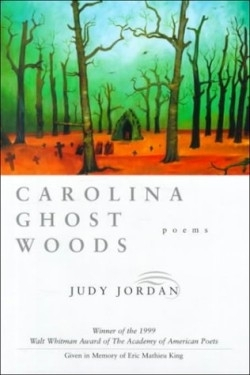

Carolina Ghost Woods

Carolina Ghost Woods, Jordan’s winning manuscript for the prestigious Walt Whitman Award of the Academy of American Poets is a walloping, gritty and fearless short collection. In a mere two dozen poems, some of them long, she presents a deeply haunted and often profoundly damaged population.

Hers is a South similar to Dorothy Allison’s fine and frightening autobiographical novel Bastard Out of Carolina except that, in contrast to Allison’s sparse prose, the poems in this text contain equal doses of beautifully figurative and rhythmic language to balance the disturbing behavior of the inhabitants of these woods. In her word world, toads crouch in “crooked caves of alder roots,” the sunset “smears into questions,” tomorrow gets blinked away in the “crow’s chalked eye,” a place smells “green-walnut bitter” and a woman “shoveling words to the black mouthpiece” of a phone announces that she shot “her man.” Jordan’s is the kind of subject matter that could put a reader off if the imagistic word-play and gripping narratives weren’t so skillful. Or if the heart of these poems were less than absolutely honest.

Jordan’s persona in these poems appears to be a broken-footed, arthritic woman of considerable spiritual stamina who is haunted by the people of her past (particularly her mother) as well as by family abuse, dysfunctional relationships and humanity’s general practice of cruelty and injustice. In “Sharecropper’s Grave,” the first poem of the first section, she introduces the graveyard, a motif to which Jordan will return. Here Jordan’s persona buries (or discovers) the dead, but here also, through the act of imagination, a diverse cast rises and speaks. In this first section, the most predominant character is the speaker’s mother, an apparently desperate woman who in “Scattered Prayers,” is the “lone kitchen match / our house burnt for the insurance; / she’s what’s left-four chimneys / and the sun breaking off the tin roof.”

This connection between the speaker and her mother beautifully threads and unites these first poems. Jordan’s strategy is a good one because readers will need these moments of compassion and the deep connection to the natural world- “I want to believe in the power of rosemary…” (“Help Me to Salt, Help Me to Sorrow”) that sustains the speaker. After the first section, she teases the reader into tougher times. “Killing at the Neighbors,” starts off a series of poems in which the speaker questions life’s irreversible moments, and the way human spirit may enter and stay- “Like a house, I was a squabble of ghosts…”

Her third section, “The Silence, The Bone-Weary Sound,” moves into a study of silence that sustains though never answers her speaker’s questions. In these poems, Jordan seems to have set out to upset the myth that silence offers serenity or peace. In these poems, silence and its cousin, sorrow, never leave, but the world does continue to evolve, and her speaker tenaciously seeks something, certainly not order-she knows too much to believe there’s order in the world-but the moments where the natural world rises and offers splintered fragments of light, “…bulbs of horseradish and sapling bitterroot / reclaim the slime-slick dam / knotted with weed and yellow broom” (“At Winter’s Edge”).

These poems are asking all the right questions, and though specifically centered on Southern topography, often morph into the universal with a simple turn of lines: “There in the distance, a pale face. / What person, with a shrug, turns away? / If I could, I’d wake / from this sleep of names, / Elam, Babylon, Nineveh, America.” In this final section, consisting of a single poem, “Dream of the End,” she expands her psychological issues into a macrocosmic vision, one that uses history and the abuse of power to explore the hopelessness faced at the turn of the century. She never gives up, however, and this resilience is the strongest aspect of her writing. There is something she must do, and she reveals it in the final lines of this poem, “Tell me a story, the round-headed boy said, / and I did, by god, in this year of our Lord, / war oncoming on all sides. Why wouldn’t I?”

These are poems that examine closely a less than admirable humanity, but do so with such sensitivity to the tenderness interrupting hard existence that the poems ring with honest vision and human truth, fallible as that may be. This is an exceptional collection.

Reviewed by

Anne-Marie Oomen

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.