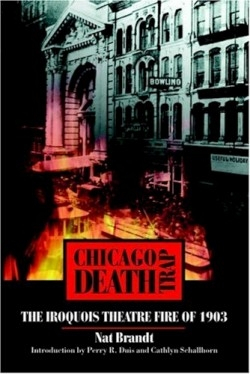

Chicago Death Trap

The Iroquois Theatre Fire of 1903

The Iroquois Theatre opened on November 23, 1903, in downtown Chicago. It was called a “virtual temple of beauty” with its foyer patterned after the Opéra Comique in Paris, its enormous stage (fifty feet deep and 110 feet wide), and seating for 1,724 patrons. On the afternoon of December 30, a fire triggered by sparks from an electric wire ignited a scenic curtain. The flames quickly spread, claiming the lives of 602 people, most of them women and children who were attending a Wednesday matinee. At the time, all the seats were filled and there were 200 standees. Eddie Foy was performing in Mr. Bluebeard, a musical comedy with a cast of nearly 300 performers and a stage crew of 200. The new theater, writes the author, had been declared “absolutely fireproof.”

Brandt, former editor in chief of Publishers Weekly, former editor of The New York Times, and author of more than ten books including The Man Who Tried to Burn New York, relates that the theater had no alarm system hooked up to the Chicago Fire Department headquarters, nor did it have a sprinkler system as required by city law. There were no signs over emergency exits. The theater lacked functioning ventilators that could carry off flames and fumes if a fire occurred on stage. Doors were routinely locked during a performance to control the movements of the audience and no one was able to leave the balconies until intermission. Brandt writes that the theater had no standard fire-fighting equipment: no hooks to pull down flaming scenery, no axes to break open locked or stuck doors, not even pails of water on stage.

Quoting a variety of sources, including Chicago police and fire department reports, accounts from fourteen newspapers, and many books, Brandt describes the “heaps of mangled and charred humanity. The dead were placed in piles on the sidewalk. The corpses were unceremoniously tossed into whatever cart or wagon was handy, and once the vehicle was filled with stacked bodies, it left for a mortuary.” He recounts the painful aftermath of the tragedy. The city closed all theaters immediately and soon shut down dance halls, dime museums, clubs, the Chicago Coliseum, and other places that accommodated crowds.

The disaster resulted in a sharp decline in tourism; the number of people entering the Loop each day fell by 25,000 in the weeks following the fire. The author writes that everyone put the blame on someone else. No one accepted responsibility. Brandt gives readers a gripping account of a tragedy that never should have happened.

Reviewed by

George Cohen

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.