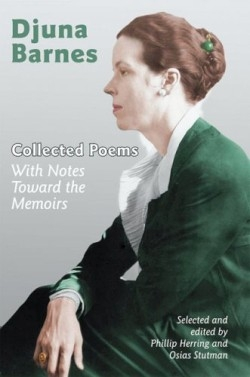

Collected Poems With Notes Toward the Memoirs

Of the author’s celebrated modernist novel, Nightwood, T.S. Eliot wrote that it possessed “the great achievement of a style, the beauty of phrasing, the brilliance of wit and characterization, and a quality of horror and doom very nearly related to that of Elizabethan tragedy.” All of these ingredients can be found in this newly edited collection, though scattered throughout much material of lesser stature.

An artist, playwright, novelist, and poet, Barnes led a genuinely tragic life. When she was a child, her father brought his mistress home to live alongside his wife, and Barnes was almost certainly molested, probably by a family member. Throughout her life, Barnes was tormented by depression, alcoholism, ill health, financial distress, and suicidal urges. Her early poetry is almost unbearably morbid. One hears echoes of Marvell, Dickinson, Edith Sitwell, and Yeats, among others. Her later poetry, with influences from the Elizabethans to D.H. Lawrence, is more skillful and bittersweet.

While her prose was experimental, Barnes’s poems were mostly conventional in structure. At the verse level, however, she excelled in conjuring highly potent images and phrases that did not always, as the editors indicate, cohere into an intelligible poem. “Discontent” marks one of the more fully realized late poems: “Truly, when I pause and stop to think / That with an hempen rope I’ll spool to bed, / Aware that tears of mourners on the brink / Are merely spindrift of the shaken head, / Then, as the squirrel quarreling his nut, / I with my winter store am in dispute, / For none will burrow in to share my bread.”

The editors provide copious notes to virtually every poem. Herring is professor emeritus of English at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, biographer of Barnes, and author of Djuna: The Life and Work of Djuna Barnes. He supplies the layer of fact critical to reading so autobiographical a writer. Stutman, a Spanish translator of Barnes, brings a poet’s sensibility to the editorial work.

Most of the late poems were unpublished and exist as multiple drafts. Many of the drafts are simply reservoirs of images, storehouses of poetic lines and phrases that Barnes used and reused in different combinations, seeking the publishable formula that would earn her a few dollars. The notes provide a record of changes, variants, and different versions of the poems probably more useful to the scholar than the general reader. Most poems include a section of “Commentary” notable for insight and sound critical judgment.

The book concludes with a densely packed non-narrative collection of memories and encounters, intended to be used later in a memoir never written. Barnes’s observations on Eliot, Joyce, Gertrude Stein, and Jean Cocteau are vivid and fascinating. Her reflections on expatriate life equal anything by the better-known memoirists of Paris between the wars.

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.