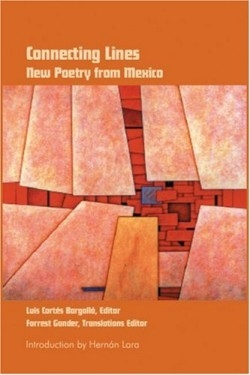

Connecting Lines

New Poetry from Mexico

To a modern polyglot who’s into traveling and culture-gawking and fond of language games, poetry in translation can be inspiring, infuriating, boring, or tedious. In this version of a pair of companion volumes growing out of a serious conference among American and Mexican poets, professors, and language buffs, poetry turns out to be just plain fun.

The book of U.S. poems offers works written by fifty American poets born between 1945 and 1971 and translated by fifty Mexican poets whose ages range along the same stretch of approximately three decades. The selection of poets chosen by the editor was inspired by her wish to “present a small sampling as rich in voices and viewpoints as American poetry and American life itself.” In addition to Lindner’s introduction, an additional preface by bilingual poet and scholar Dana Gioia celebrates the growing collegiality of the arts and artists of the United States and Mexico: “It has taken politicians centuries to realize the vast and unbreakable human connections that unite our two nations, but ordinary individuals on both sides of the border have long recognized the special bonds.”

These few lines from “Refrigerator,” by Thomas Lux, close an elegantly simple and apparently mundane musing on a jar of Maraschino cherries in the family refrigerator: “They were beautiful / and, if I never ate one, / it was because I knew it might be missed / or because I knew it wouldn’t be replaced / and because you do not eat / that which rips your heart with joy.”

An equally simple and elegant translation by Argentina Rodriguez might well rip the reader’s heart with joy and leave in mind the question of just who is this Argentina Rodriguez, as she is not represented among the poets in the volume of Mexican poetry; two well-known American poets, Carolyn Forché and Jorie Graham, are represented in both these books. But then it’s not every bilingual poet who has the nerve to hazard writing poems, or even translating them, in both languages.

The straightforward accessibility of Lux’s poem is offset by one from much-younger poet A. E. Stallings, whose “Hades Welcomes His Bride” is in impeccable iambic pentameter and “Study in White” in a complex rhyme and equally metrical stanzas. The translations by Mario Murgia make no effort at all to reproduce the metrical elements of the originals. The same is true of other metrical poems, and raises the serious question of what should be looked for in translations of formal verse. The selection of fifty such different poets and equally different translators for both volumes spreads out a whole playing field for speculation that should lend opportunities for joyful reading and serious discussion.

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.