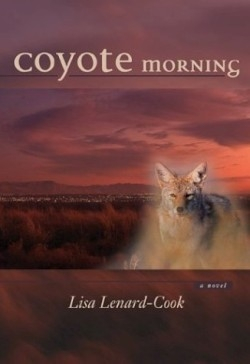

Coyote Morning

Though the coyotes that so magically appear and disappear to the startled residents of this small community near Albuquerque, looming like silent totems, are not quite trespassers, a few locals bluster in letters to the newspaper that they will shoot them to protect life and property, for “the only good coyote is a dead one.” Called “God’s dogs” by the Native Americans, in tribute to their original indigenous domain, now these animals, much like the Indians, must adapt to their new landlords, who hunt and haunt the outcroppings of Wal-Mart and strip malls, a baleful reminder to the lapsed practice of peaceful coexistence.

Wary as scorned lovers, feral yet domesticated, man and animal live in a fearful symmetry. And however adaptable, intelligent, and roving these creatures prove to be in eluding their captors, their fate is only a minor version of the lives of the story’s two women, who are equally beset with alpha-male troubles: Alison and her impressionable daughter Rachel have been rudely abandoned by her roguish husband, Chris; Natalie, living modestly on her New York parents’ inheritance, suddenly finds her charming, feckless brother Sherman on her doorstep in need of safe harbor. Between these two male paragons is Ralph, a Vietnam vet local animal control operator, whose orders to shoot an aged alpha-male coyote are subverted by his long standing covert “trap and release” humane relocation of his quarry.

Despite Chekhov’s dictum that any loaded gun shown in Act I must go off in Act V, no red-blooded coyote, human or animal, comes to any harm in this book. Indeed, not enough really happens. The social observations are deft and acutely delivered, but these laconic drifts of dialogue (all without quotation marks) don’t generate much heat or pace. The electric moment of a coyote leaping off a pick-up truck bed into the wild leaves the characters, and the reader, with a sense of abandon and awe. A howling coyote wakes Natalie and Sherman in the last pages, but their few shared words about their New York childhood are mostly Natalie’s silent monologue about her emotionally repressed life; Sherman is still an emotional cipher. In effect, that moment summarizes the novel’s difficult task of transposing an almost effete New England restraint into a Western locale.

The author, who holds an MFA from Vermont College and is now a resident of New Mexico, has acclimatized her empathy for mute animals in this, her second novel (the first, Dissonance, won a local literary prize), but these coyote sightings do not avoid the larger stylistic trap of sentimentality. That’s a beginning to a larger novel, or, in this case, the conclusion to a quieter one.

Reviewed by

Leeta Taylor

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.