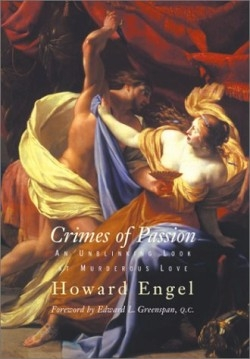

Crimes of Passion

An Unblinking Look at Murderous Love

For the thrill-seeker, murder doesn’t always measure up to expectations. We can hope for a power-crazy ex-commando indulging in a dramatic axe assault but may get a flat-footed meter-reader wielding a poisoned muffin. In fact, love and passion seldom soar in the thirty-five cases the author presents. A majority of these people-who killed a parent, spouse, troublesome lover, or unwanted mistress-are marked by the characteristic “banality that attends most domestic crimes.” Nonetheless, Engel offers a useful compilation that will both expand and correct the thoughtful reader’s understanding of le crime passionnel, passionless though many prove to be.

In this study Engel focuses not upon gory retellings of the killings but on causative factors, breakdowns of self-control, premeditation, exculpatory conditions, the double standard, the trickiness of statute law, and the social climates in which French, English, and American juries operate. He notes that his material is “eclectic, not systematic… a medley, a tsimes.”

In an earlier exploration of criminal justice, Toronto-based Engel wrote The Lord High Executioner: An Unashamed Look at Hangmen, Headsmen and Their Kind (Firefly 1996). He has won many fans (and a number of prizes) with his multi-title series featuring the engaging, laid-back crime investigator Benny Cooperman.

Engel is at his best here in his two French cases, those of Madame Caillaux, who in 1914 shot a newspaper editor given to trashing her politician husband in print, and Madame Chevallier, who in 1951 calmly shot her errant husband, also a politician. The two illustrate Engel’s assertion that “women tend to murder their victims in public places and then make no attempt to escape.” These strong-willed ladies did not have to; both received the acquittals they expected.

Ruth Ellis (the last woman to be hanged in Britain) and Jean Harris receive interesting comment. Of widely different backgrounds, status, and resources, they suffered similar victimization-but their sentences reflected very different judicial climates. Engel deals too briefly with too many of his other cases. Readers know of Leopold and Loeb, Lizzie Borden, Crippen, and Lorena Bobbit; they are far less likely to know of Workman, Watkins, Belshaw, Hogg, and a dozen others. Nonetheless, where contextual information is scant, Engel’s comments on legal points and process save the day. His statistical summaries give pause for useful thought.

Rare photographs and excellent design and production make this an elegant book; notes and an extensive bibliography give it a resource-and-research value, particularly for spouses who eye the ice-pick during a tense pre-dinner drink.

Reviewed by

Peter Skinner

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.