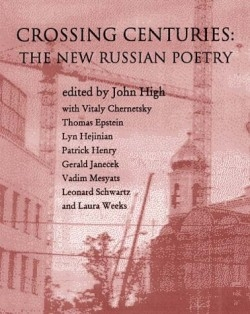

Crossing Centuries

The New Generation in Russian Poetry

“Man, society, and the nation cannot fully exist without an attempt at self-understanding,” writes Kirill Kovaldzhi in an essay describing the state of poetry in Russia at the end of the 1990s, a time when poetry returned to its usual struggle for survival, this time in the face of its “most potent rivals”: the television, VCR, computer, and CD-Rom. Kovaldzhi’s concern follows a period in the 1970s, when “poetry grew larger than itself,” drunk on the absence of the usual censorship. Symptomatic of this shift from language for the purpose of propaganda to language as revelation, were the masses of young fans who flocked to overflowing stadiums for poetry readings, signaling a social and political phenomenon, as much as an artistic one. Then, and still, the poets of Russia were doing what poets have always done: to put language in the service of improved understanding, both on a personal level and in terms of the nation at large. Society, however, is always in a state of flux, and trends move on, hence Kovaldzhi’s concern.

Opening this expansive anthology of Russian poetry is like accidentally discovering buried treasure. Part manifesto, part offering, and many parts inspired creation, the poems are political and apolitical, formal and utterly experimental, making it difficult to accurately characterize the diversity represented in more than 500 pages of new or unfamiliar work, much of it appearing here in English translation for the first time. In a country where language and all forms of creative expression have too long suffered the constraints of totalitarianism, a collection documenting the gradual unfettering of voices belonging to a newer generation of Russian poets is a gust of new air into a musty room. As John High states in the introduction, “Nowhere in known history has a nation of writers been so systematically brutalized, tortured and murdered than in twentieth-century Russia. Murdered, but not silenced or stopped at the boundaries of language, where another world converges.”

The abundance of writing produced in the time approaching and immediately following the collapse of the soviet system of government is staggering and noteworthy. This book offers an extensive overview of a vital literary and intellectual culture, as well as an avenue by which to understand socio-political discourse and history as it unfolds in present-day Russia. Here, the relationship between art and life is declared, denied, celebrated and abhorred, and the means by which these poets implement their versions is both instructive and reassuring. Though the poets of note are too numerous to mention, several voices stand out above the rest. Among the conceptualists, who saw the poet as collector and assembler as opposed to inventor or creator, is Ivan Akhmetev, who wrote many succinct and thoughtful pieces, including this one line poem: “Forgot to write it down.” Representing the Metarealists with her belief that no subject is “below poetry: everything is recuperable, everything is real” is Elena Shvarts, thought by many to be the most talented among her generation.

Nina Iskrenko, an active member of the famed Moscow Poetry Club of the 1980s, was eccentric and committed to the avant garde. Despite her premature death, Iskrenko’s influence continues to be felt among the most experimental writers in Russia today. A member of the Polystylists, she said “Art provides us with a unique opportunity, first of all to believe in everything, and second, third, and forty-ninth of all to tell everyone about it.” Iskrenko, like so many of the poets in this collection departs from convention both in terms of subject matter and syntax, often creating visually graphic poetry forcing the reader to encounter the text in new ways.

Navigating this array of movements and voices is made manageable in part by pedagogical essays aimed at familiarizing the reader with the relevant techniques and influences. Covering topics such as “Glasnost & the Resurfacing Gay Poetic” and “The Dilemma of Women’s Voices,” thoughtful prose by scholars, translators, and poets is interspersed throughout the book, creating a context within which the poetry itself has even greater heft. The poets in Crossing Centuries clearly hold their forebears in high regard, making frequent allusions to Pushkin, Mandelstam, and Tsvetaeva among other esteemed authors of the past. The tradition of literature represented by these figures alone is robust and significant both in national and international terms. One has reason to believe that such standards of creative achievement were upheld by their compatriots at the end of the twentieth century, and will continue to be nurtured into the new millennium as well. This book does much to bolster the awareness of an emerging and important milieu and should not be ignored in its admirable efforts.

Reviewed by

Holly Wren Spaulding

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.