Daddy Hall

A Biography in 80 Linocuts

- 2017 INDIES Winner

- Honorable Mention, Graphic Novels & Comics (Graphic Novels & Comics)

Daddy Hall’s richly lived life is captured in linocuts that are both brutal and poignant.

Tony Miller’s Daddy Hall: A Biography in 80 Linocuts is a potent visual storytelling project that captures the outsized life of the African/Native American/Canadian folk hero.

John “Daddy” Hall’s life not only spanned three cultures, but two countries (the US and Canada), two wars (the War of 1812 and the US Civil War), five or six wives, twenty or so children, and three centuries (1793-1900). That’s right; the arithmetic shows 117 epic years, packed with a lot of action.

Art professor George A. Walker, who attended college with Miller, fills in essential backstory details about Daddy Hall and his artist-biographer, as well as a nutshell art history of linocuts, expressionism, and the tradition of wordless narratives. Daddy Hall was the son of an African-American mother and a Native American father and, as legend has it, he escaped not just once, but twice from American slavers. He ended up settling in Owen Sound, Ontario, an Underground Railroad terminus, where he enjoyed a life of freedom among other formerly enslaved Africans, British Loyalists, and Ojibwa neighbors. There, he befriended two of Miller’s great-great-grandfathers—another impetus for Miller’s artistic exploration of Hall’s exploits.

A bouncy preface by poet George Elliott Clarke and an afterword by art gallery director Tom Smart divulge more clues about Miller’s interpretation of Daddy Hall’s life, so that the “magical alphabet” decoding and celebrating his odyssey can be more readily interpreted.

Linocuts are a wonderful medium for this dramatic subject; contrasts of black and white are a perfect visual metaphor for artificial social divisions between people of different skin colors. The sharp lines and stylized silhouettes of the printed images are effectively used to express violence and suffering, as in the book’s many brutal images of enslavement, torture, and hand-to-hand combat. Miller’s range also extends to images of great beauty and poignancy, like his linocuts of Daddy Hall kissing and holding his wives and children, as well as the quiet grandeur of African and Native American ancestors and family members in traditional dress.

These peaceful times are the exception in Daddy Hall’s saga, and most of Miller’s visual biography is riven with sorrow, hatred, and pain. A repeating, ominous theme of tall-masted ships and white men in tall hats signals that trouble lies ahead. The most awful, most powerful images depict the inhumanity of the slave system, with scenes of whippings and people bound to poles or wearing horrible, but historically accurate, barbed metal masks. These images are uncomfortable to look at, but as Walker notes in his introduction, “We need to tell these old stories of struggle and perseverance in the diaspora so that we can grow from them.”

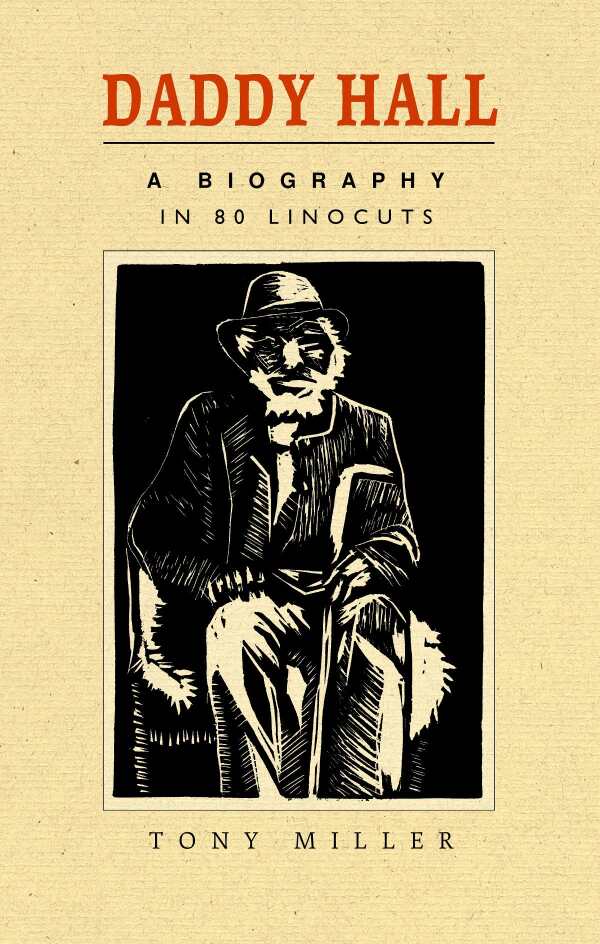

Legend has it that Daddy Hall ultimately found peace and happiness in his later years at his Canadian home, summed up so satisfyingly in Miller’s final image of the centenarian, which also appears on the front cover. It’s a fitting endpoint for this richly lived life, imagined by a virtuoso artist employing a dramatic “iconography of liberation.”

Reviewed by

Rachel Jagareski

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.