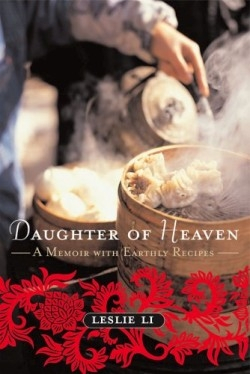

Daughter of Heaven

A Memoir with Earthly Recipes

In her preface, the author warns her readers not to expect what she calls a “typical cookbook.” In fact, she professes a loathing for the kitchen and a late start in the preparation of the Chinese cuisine that is the book’s ostensible focus. In fact, while food may be the inspiration for this memoir, the recipes included at the end of some of the chapters are more a dessert than a main meal for readers.

The author’s awareness of food, particularly Chinese food, doesn’t really become apparent until she decides to write a biography, which eventually became her first novel Bittersweet, about her paternal grandmother, Nai-nai, who lived with the author’s family for several years in suburban New York before returning to China and dying at the age of 102. Nai-nai is the first wife of Li Zongren, a vice-president under Chiang Kai-Shek. She’s from peasant stock, and her life, like her cooking, is paradoxically both simple and complex. She turns the American Li home into her vegetable patch, transforming the author’s girlhood sandbox into a place to grow bok choy. She gathers weeds, or gow-gay , along roadways, and adds them to fragrant soups.

As an adolescent, Nai-nai’s granddaughter is fascinated by her grandmother’s fortitude, at the same time as she is mortified by her behavior. The girl’s reaction is rendered complicated by her ethnicity. As a minority in Riverdale, New York, Li grapples with the piteous and not uncommon self-loathing that many non-white Americans harbor. Much of this feeling is manifested in the difficult relationship she has with her father, Nai-nai’s son. The man has his own personal demons (it isn’t easy being the son of a famous politician, even in a foreign country). To some readers, his disciplinary techniques and strict rules may seem misguided, and some are; but as the author explains, much of what he does is very “Chinese.” He has an American life but a Chinese soul.

It’s this dichotomy within herself that the author struggles to accept. At one point in her adulthood, a knick-knack vendor in New York’s Chinatown tells the author that she is juk sing, one of the “Chinese who no speak Chinese. Chinese who look Chinese no act Chinese. No culture inside.” Such an assessment could be hurtful, and it is, but the author turns it around, seeing art in the emptiness, which is illustrated later in the chapter as Li studies a Chinese scroll of a bamboo sapling and contemplates the fullness of its negative space. While some of the memoir’s dialog can be stagy, the book compassionately recounts the author’s journey to an acceptance of herself.

Reviewed by

Olivia Boler

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.