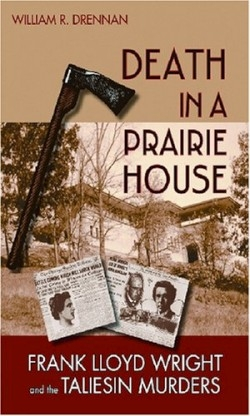

Death in a Prairie House

Frank Lloyd Wright and the Taliesin Murders

“Law and rules are made for the average…it is infinitely more difficult to live without rules, but that is what the really honest, sincere thinking man is compelled to do.” With these words, Frank Lloyd Wright summarized what he saw as his place in the world, and this view is abundantly illustrated in the story of Wright’s house, called Taliesin, in Spring Green, Wisconsin. When, in September of 1911, he left his wife and moved his married paramour, Mamah Borthwick Cheney, into the house, the neighbors in the small town thought they had seen it all. Little did they know that almost three years later, they would see the single most horrific act of mass murder in Wisconsin history overshadow Wright’s shocking “love nest.”

This is the story of Wright’s rise to fame, his disregard for the social mores of the time, and the brutal murders of seven adults and children that dramatically impacted Wright in both his life and his work. The murders were committed by Julian Carlton, the African-American butler at Taliesin who felt that one of the construction laborers had insulted and abused him the day before. In the end, Taliesin was burned to the ground, and Mamah, her two children, and four laborers were dead, including the man who had insulted Julian. Wright was in Chicago at the time, working on the construction of Midway Gardens. Although the authorities caught the perpetrator, there were many theories about why he committed the crimes. When his capture became imminent, Carlton drank muratic acid. He only lived a few months after that, and while he was hastily convicted for the murders, his death only added to the rumors that swirled around Wright.

Drennan is a professor of English at the University of Wisconsin. His notes and bibliography are extensive, and he delves deeply into the questions that surround the tragedy. He also writes a great deal about Wright’s career, both before and after the murders, discussing at length the changes in his architectural style. While this book is intriguing for its topic alone, it sometimes suffers from too much architectural jargon. True crime fans, however, will be drawn to the massacre’s details such as the pouring of gasoline under the dining room doors, the lighting of the match, and the bludgeoning with an ax of escapees exiting through the window. Architectural aficionados will enjoy the copious design and construction details.

This is a fascinating topic for true crime readers, and if they are patient, they will be ultimately rewarded with an intriguing, little discussed crime that truly changed the face of American architecture.

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.