Devil's Paintbrush

One's Past Doesn't Predetermine One's Future

A story of trauma and triumph after enduring trials in childhood and war paints a path to recovery for other sufferers of PTSD.

A work of fiction that follows the writer K. L Arthur’s own personal story quite closely, The Devil’s Paintbrush illuminates one man’s battle with post-traumatic stress disorder and strives to empower other sufferers to, as the main character urges, “give themselves permission to sprint vs. crawl.”

Ken Callahan is a little boy who has learned to be on alert at all times. Born into family circumstances far too horrifying for a child, let alone most adults, to grasp, he keeps his defenses up and his voice as submissive as possible. He must survive in a dysfunctional family jungle, dominated by a violent, older half brother who takes pleasure in suffocating him. With no father in the home, Ken’s mother “needed a bottle, a cigarette, a dollar, and a man nearby at all times.”

In a poignant episode, Ken makes his way home, alone, from Summer Breakaway Camp after his mother fails to pick him up; he learns that she has moved with no notice, and he must cadge a few nights’ sleep on a neighbor’s couch. Such survival skills come in handy later in the real jungles of Vietnam, where Callahan’s valor in combat earns him the Bronze Star. The guilt of surviving in the face of death when others did not compels him to seek help; the latter portion of the text focuses on his attempts to rehabilitate himself.

As a work of fiction, the book struggles under its own weight. The brutal saga of Callahan’s childhood and early adult years is composed primarily of lengthy narrative passages with little dialogue. The book is too long, overly laden with minute personal detail that deviates from the central plot, which could have been conveyed effectively in half the pages. The story jerks back and forth from Callahan’s childhood to his army service and to his more recent experiences, with few handholds to move the reader along. There are also word-usage errors, such as “sewed this seed.”

However, the primary audience for the book will likely be those who have suffered from psychological setbacks and who will take inspiration from how Callahan learns to overcome his blighted past. Reluctantly, he accepts therapy for PTSD suffered from his war experiences and then hangs on as he gradually, painfully acknowledges that much of his trauma stems from his tormented childhood.

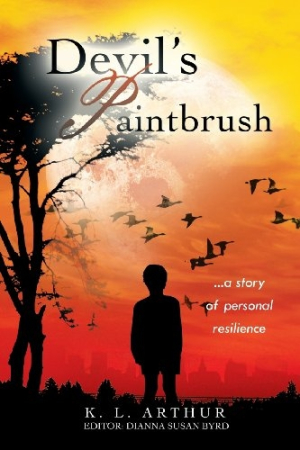

Fortunately, Devil’s Paintbrush offers hope and is written by someone who has succeeded on all counts and wants to help others do the same. The volume’s cover is evocative: a skinny kid watching a flock of geese in free flight over a shadowy city landscape. The title references a brightly colored flower that grows in “hostile climates” all over the world.

While not the easiest read because of the harrowing emotional and physical abuse described, The Devil’s Paintbrush can offer guidance for survivors of child abuse and sufferers of PTSD. Arthur is a corporate trainer who has written nonfiction books about overcoming personal challenges; this latest work could serve as a useful tool in his professional activities.

Reviewed by

Barbara Bamberger Scott

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.