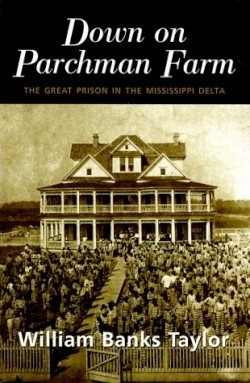

Down on Parchman Farm

The Great Prison in the Mississippi Delta

In the early 1970s, a series of federal court orders led to the dismantling of Parchman Farm, a prison as legendary—even notorious— as Alcatraz and Sing-Sing. The demise of this turn-of-the-century dinosaur, a throwback to the antebellum cotton plantation complete with shuffling black laborers and whip-toting white overseers, was a triumph for decency and social justice… wasn’t it?

Not necessarily. In this refreshingly balanced study, Taylor meticulously retraces the history of Parchman Farm and concludes that, despite its many faults, it was not always the chamber of horrors depicted by its civil rights-era detractors. Just as significantly, he makes a strong case that the towering concrete cellblocks, razor wire and modern corrections philosophy that replaced the old Parchman have left neither its inmates nor Mississippi’s taxpayers better off.

To accept Taylor’s premise, one must view Parchman Farm, and officials such as Governor James K. Vardaman and prison superintendent Marvin Wiggins, in their historical context. By today’s standards Vardaman was shockingly racist. A firm believer in black inferiority, he was elected in 1903 and became “the philosophical and political architect” of Parchman and the rest of Mississippi’s penal system, considering them essential to the preservation of white rule and social order. Still, for his time he was a radical reformer who opposed brutal treatment of prisoners and fought to provide them with decent food, education and health care.

Wiggins, who ran Parchman during its heyday from 1944-56, was no less of a paternalistic white supremacist, yet brought about such innovations as adult education, an inmate newspaper and the nation’s first prison furlough program. With adequate funding and a profitable farm operation, Parchman at mid-century was a model of penal efficiency where the inmates, although worked hard and disciplined severely for misbehavior, served their time under generally humane conditions. Gradually, however, a combination of scandals, political infighting and social change doomed Parchman Farm. Whether for good or ill, let the reader judge.

Students of history and American culture will find this a fascinating and entertaining work. As suggested by the many footnotes, Taylor has researched his subject well and livens up the narrative with colorful descriptions of politicians, inmates and other key players. Particularly enjoyable are his descriptions of everyday prison life, complete with lingo such as “Rosie” (a generic term for women), “Black Annie” (the lash), and “rabbit in the row” (an inmate who attempts escape). Lyrics from blues songs about Parchman and references to the prison in the novels of William Faulkner and Shelby Foote are interspersed through the book —proof that, although the Parchman of old is gone, it has attained immortality through the rich, enduring folklore of the South.

Reviewed by

John Flesher

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.