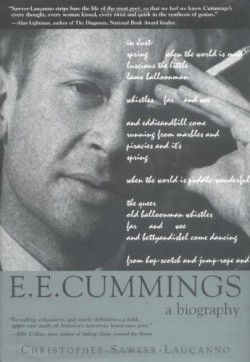

E.E. Cummings

A Biography

Even people who don’t really like poetry have a favorite E.E. Cummings poem. Playful, idiosyncratic, and iconoclastically original, Cummings is unique, his work perhaps the most instantly recognized of all American poetry. Yet as this first-rate biography makes clear, its often childlike charm masks a relentless determination to expand language and meaning—as indeed the poet’s own bohemian charm masked a sometimes breathtaking egocentricity.

The author is ideally suited to his subject. Longtime writer-in-residence at MIT, he is himself a poet and translator, as well as author of several books including a well-received biography of Paul Bowles and a study of American writers in Paris after World War II. Sawyer-Lauçanno knows Cummings’s territory, from New England and New York to France and Italy; in addition, his access to much previously unpublished material lends additional authority to what is surely the definitive study of the poet and his work.

Edward Estlin Cummings was born in 1894 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, scion of an upper-middle-class family whose friends included Harvard luminaries like William James and Josiah Royce. After a classical early education, Cummings joined the Harvard class of 1915, where he was active in literary affairs; his friends included poets John Dos Passos and Robert Hillyer as well as several wealthy aesthetes who played important roles in later decades. Cummings had not yet found his inimitable style; his Harvard poetry grates on the modern ear, filled with “thees,” “thous” and late-Victorian sentimentality. He was also a gifted painter, a talent that sometimes earned him more than his poems. Sawyer-Lauçanno evokes well Cummings’s fascinating holistic approach to all art: to him, canvases and poems were all of a piece, different facets of the same creative vision.

In early 1917, he wrote the first poem to capture the voice he came to be known by: “Buffalo Bill’s / defunct,” a favorite to this day. He also took the only regular job he ever held, at Collier’s magazine, where he lasted just two months before resigning. Soon thereafter, America entered World War I and Cummings, a pacifist, volunteered for ambulance duty, but his anti-war, anti-authoritarian attitude so irritated his superiors that he was interned by the French for sedition, an experience that resulted in his remarkable memoir, The Enormous Room.

Upon his return to America, Cummings soon became the character known to history, both as poet and person. He took up painting and writing again, with his rich Harvard friend Scofield Thayer as patron—and Thayer’s wife, Elaine, as mistress, by whom he had his only child (who didn’t learn her true paternity for many years.) Surprisingly, this unusual ménage didn’t destroy their friendship: Thayer continued to promote the poet’s career and “lend” him money; later, Elaine became Cummings’s wife, the first in a series of tumultuous relationships.

During the 1920s, Cummings was hailed by the avant-garde but earned little, and depended mostly upon the generosity of family and friends to finance a life mainly divided between Greenwich Village and Paris, where he preferred such company as Ezra Pound and the Dadaist Louis Aragon to that of the “Lost Generation” American expatriates (though he knew them all). By 1930 he had divorced, remarried, and published several remarkable collections of poetry as well as a play. Soon after, he traveled to Russia to witness the Soviet experiment; the resulting book surprised and angered those who had assumed that Cummings’s radical poetic style implied equally radical politics. Ever the individualist, Cummings confounded them—as indeed he delighted in confounding the doctrinaire of every stripe. This pattern of fierce creativity, emotional upheaval, deep friendships, and perpetual impecuniousness continued, though his earnings eventually grew with his fame and his stormy love life settled down somewhat after his second divorce when he met Marion Morehouse, his companion until he died in 1962.

Sawyer-Lauçanno deftly balances biographical fact and poetic accomplishment, presenting a man perhaps best captured by the term enfant terrible. The author is frank about Cummings’s failings—among them a childish self-centeredness, financial irresponsibility, and a nasty streak of anti-Semitism—but he also summons Cummings’s genius for friendship and his absolute devotion to his art. In addition, he does a wonderful job of reminding readers how extraordinary Cummings’s poetry was at the time (and how inimitable it remains to this day). Sawyer-Lauçanno’s well-chosen explications de texte offer a wide-ranging appreciation studded with insights into the most important examples of the poet’s originality. A wise reader will have The Collected Poems at hand for greatest enjoyment, but this is by no means necessary: this book can easily be savored on its own merits, and the endnotes offer scholars a cornucopia of additional information.

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.