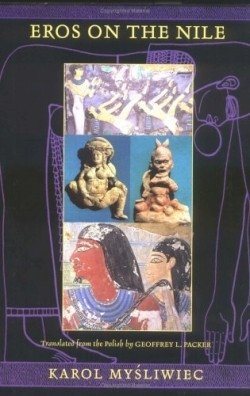

Eros on the Nile

He who could hold that body tight / would know at last / perfection of delight— / Best of the bullyboys, / first among lovers.

Caveat lector! Fittingly, this book, like Eros, offers its greatest rewards to the persistent: the half-hearted reader will remain unfulfilled.

Eros was surely more pervasive but less prurient in Ancient Egypt than in Greece of the erotic painted vases or Rome of the imperial orgies, yet few accessible and reader-friendly studies exist that present Eros as a force in Egyptian religion and daily life. The entire civilization, fixated on fertility and regeneration, with sexually active deities, was wed to both the fecundity and erotic dimensions of Eros: art, artifacts, and literature were strikingly sexual. Fortunately, the author, who is director of the Department of Egyptian Archaeology at Warsaw University, and author of the well-received Twilight of Ancient Egypt, is an expert guide and commentator.

In discussing the births of the gods (“the fundamental problem in theogony”) and their role in ensuring continuing fertility, birth, and regeneration, Mysliwiec presents the three regional cosmological systems that shaped (or rather, complicated) the deities’ sexual roles and relationships. Mysliwiec anticipates the reader in noting that clear and validated information on the earliest religious concepts and their sexological correlates is “far from complete.” It might be an understatement to use the term “problem” to describe a conceptually challenging situation in which a god’s rape of his mother-to-be ensures his birth—a sort of pre-existence guarantee of existence. Autogenesis took other credulity-straining forms: a god might sire his own father or self-create through masturbation. These and other aspects of impossible sexual behavior (some illustrated) invariably emphasized the cycle of fertility, birth, and rebirth.

This traverse through the thickets of theogony, including probable homosexual relations between gods, leads to easier ground: Atum, Nut, Hathor, Isis, Osiris, Horus and Seth, Bes and particularly Min, an important fertility god, assume their familiar roles. The well-established cult of fertility, characterized by full-breasted, broad-hipped figurines and ithyphallic males and the pharaoh’s epithet of “mighty bull” become comfortably familiar; the frequent references in religious texts to phallic cults, copulation, and fertilization become understandable.

The second half of the book brings fertility, sexuality, and Eros from theological realms into daily life. Mysliwiec’s account of Apis, the sacred bull, and his successors (selected by means of twenty-nine distinguishing signs) and the rituals (illustrated) in which pharaohs suckle udders of the bull’s cow-mother and the breasts of goddesses to enhance personal and symbolic fertility, is particularly striking. In the palace, however, the complex responsibilities, rivalries, religion, rituals, and propaganda needs that governed domestic life suggest that neither pharaoh nor queen (“god-wife”) could expect much domestic peace and quiet. Yet numerous tomb-paintings and informal, evocative line drawings of domestic life (whether of pharaohs or commoners) hint at an enviable tranquillity.

In the section called “Religion and Magic in Daily Life,” Mysliwiec weaves a glittering thread of fact and comment on Egyptian ideals of beauty and the unashamed presentation of the body (assisted by “sacred intoxication”) and provides a fine introduction to erotic poetry (“such thighs as hers pass knowledge / of loveliness known in the old days”). This poetry, among much else, describes the wiles women have practiced since the morning of the world. Short, balding men with weak chins can take hope: the richly erotic Turin Papyrus shows an archetype physically connected to emotionally detached women.

The final chapter, “Sexual Life and Restraints,” takes the reader directly into Egyptian life; sexual mores (generally considerate), marriage, erotic love, pregnancy, gynecology, nutrition, and health care—all made fascinating through deft handling. Egyptian maxims remain timely: “Do not go after a woman / Let her not steal your heart. If she does, then … Love your wife with ardor / Fill her belly, clothe her back.”

Many of the book’s one hundred illustrations, which variously capture the sexual aspects of theogony, depict impossible erotic and autoerotic acts, and portray the sexual and fertility aspects of religion, will prove new to readers. Here, as in the text, knowledge of Ancient Egypt would be an asset. The many who lack this advantage will find Mysliwiec’s far-ranging explorations (elegantly translated by Geoffrey L. Packer) an exhilarating avenue to deeper understanding.

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.