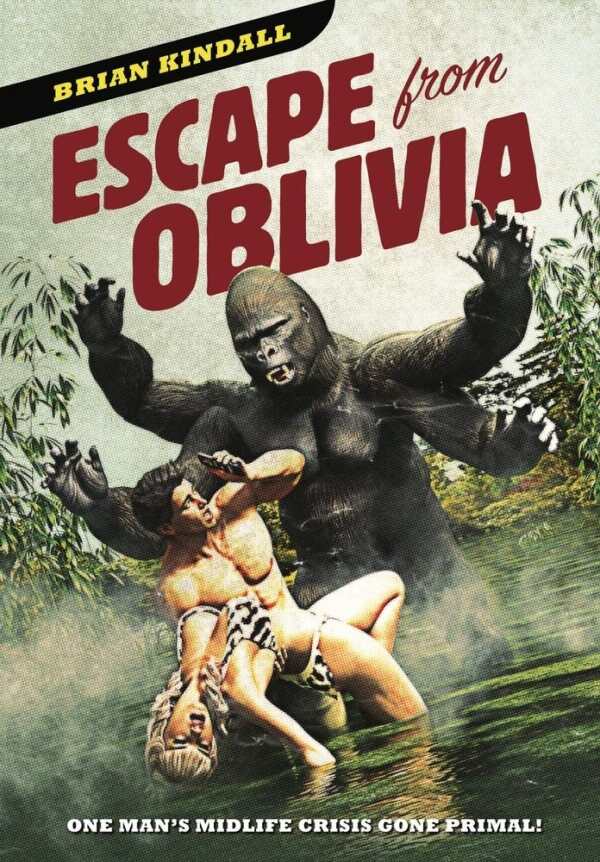

Escape from Oblivia

One Man’s Midlife Crisis Gone Primal

In the novel Escape From Oblivia, a man flirts with his long overdue maturation, but faces obstacles both real and imagined in the process.

Brian Kindall’s novel Escape from Oblivia uses humor to address the romantic, personal, and creative consequences of an average man’s haplessness.

Will struggles with reality. He’s middle-aged, married, and mired in a personal slump—“a man-shaped island of personal bewilderment.” He also doesn’t have much to show for himself at his age, and he knows it. He wrote a Western novel that became a cult classic, but his wife, who’s a lawyer, is the one who supports their family, while his second project (a biography of pulp novelist Richard Henry Banal), leads him into a fantasy-laden world of leopard print-wearing women, brutal savagery, and natural disasters.

As Will contends with his fears about mortality and irrelevance, he’s tempted by two women, both of whom are half his age. They titillate and terrify him. As he delves into Banal’s journals, he finds evidence of a magical island, Oblivia, where men are called on to use their wildest, most politically incorrect instincts to survive. Drawn by Oblivia’s lure, Will sets out to transform himself from “a chubby, geriatric dugong in a sea of supple marlin,” with humorous results.

The novel is packed with lush pulp fantasies and descriptions. Hypersensitive Will, who has an overactive imagination, grapples with his dull reality by grafting Kama Sutra-esque visions over his daily routine, perusing the assortment of mom butts at his daughter’s ballet practice to daydreaming about the core strength of his youth. As his fascination with Oblivia intensifies, conflicts blossom in every area of his life. The women who know and tolerate him, including his wife and daughter, share their pragmatic perspectives on his behavior, which contrast with the ways he sees himself. They are foils for Will’s vacillating self-aggrandizement and self-loathing.

But although the book makes frequent nods to prefeminist literature, its objectification of women is stale. While Will pines for the days when “men were men” and mourns his flaccid masculinity, the women in his life are defined in terms of how they serve his needs. Martine, a sexy French librarian, is his love object; Roxanne, a super fan, fetishizes his so-called career. Even Banal’s daughter’s worth is defined first by her sexual appeal, then by her proximity to her famous father. This deflating trope is repeated throughout the book and undermines its humor. While Will flails through his midlife crisis, his growth only extends as far as himself. Oblivia looks better and better—certainly easier to pursue than meaningful change.

In the novel Escape From Oblivia, a man flirts with his long overdue maturation, but faces obstacles both real and imagined in the process.

Reviewed by

Claire Foster

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.