Fallingwater

- 2011 INDIES Winner

- Gold, Architecture (Adult Nonfiction)

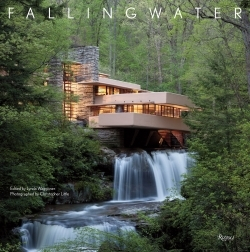

“Seventy-five years after its inception, Fallingwater affirms architecture’s prospect to engage the lyrical and visceral dimensions of human experience that arise from a direct engagement with nature.” So writes John M. Reynolds in his essay for Rizzoli’s lavish new book about America’s most significant residence. Frank Lloyd Wright’s masterpiece, the weekend house for the family of Edgar Kaufman, Sr. in the Allegheny Mountains of Pennsylvania, forever changed the nation’s built landscape while elevating our notions of what it means to dwell.

MOMA held its first major one-building exhibition in 1938 to celebrate its singular achievement, and in 1991 members of the American Institute of Architects voted it “best all-time work of American architecture.” Most modernist buildings of the era separated humans and nature, treating the outdoors like a canvas and promoting an intellectual rather than sensual appreciation. Fallingwater, on the other hand, did what Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman had prescribed for our spiritual well-being by providing a genuine connection with nature. This same belief—in the unity of, and appreciation for, all living things—forms the basis for today’s sustainability crusade.

Fallingwater’s composition is relatively straightforward: a central core of stone with massive concrete terraces cantilevering outward like branches, essentially presenting house as tree. From there, however, this simple concept gives way to the most sophisticated and nuanced rendering for a residence ever, for Fallingwater is sited atop of a series of waterfalls. And while this image has certainly been the money shot for artists and photographers since it opened to the public in the 1960s, it’s a deceptive representation of the home’s essence.

Although its appearance can’t help but delight, Fallingwater was not primarily meant to stimulate our visual capacity. Rather, the house was designed to speak to our sense of hearing above all else. In Neil Levine’s essay for the book he explains, “Hearing takes time and gives to time a depth that vision lacks,” indicating that the house’s potential for a temporal dimension most fascinated Wright.

The architect’s orchestration included the notion of physical passage, as it describes the approach to the house through the woods as well as the movement of people through its spaces, but it also referred to the more ephemeral passage of the seasons and specifically to the movement in time of the massive amounts of water surrounding the house. From within Fallingwater, we can literally listen to time pass and this opportunity for contemplation has the power to direct our thoughts about such philosophical subjects as mortality.

Lynda Waggoner, the director of Fallingwater and the book’s editor, has assembled here a sensitive portrait of a very special place. Thoughtful essays by contributors range from coverage of the Kaufman family history to Wright’s organic interiors to the building’s structural limitations. Waggoner’s own article culminates in a series of captions accompanying more than 150 pages of worthy photography. For architect and designers Fallingwater is like the most delectable of chocolates; and for those first encountering the power of architecture to thoroughly transform our lives, the taste will likely become addictive.

Reviewed by

Julie Eakin

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.