Family History (1860-1950) of a Doctor's Daughter

Ancestral voices come through clearly in this work that will engage students of period histories.

In matter-of-fact prose, Diana Walstad’s Family History (1860–1950) of a Doctor’s Daughter follows the author’s ancestors as they immigrate from Scandinavia to the United States and travels across the decades to World War II, including the historical events that influenced their lives. Three generations of the author’s ancestors find their way in America, through struggles, marriages, children, illness, and health, in these stories, told in order mostly by decade.

Each chapter includes historical information to place the ancestors in their settings, like a chart of the “Top Ten Occupations of men who left the Netherlands between 1835 and 1880,” and three intriguing paragraphs about the Frontier Nursing Service. There’s even a section on “Sex in Scandinavia,” describing the social changes these people encountered when they came to more puritan America.

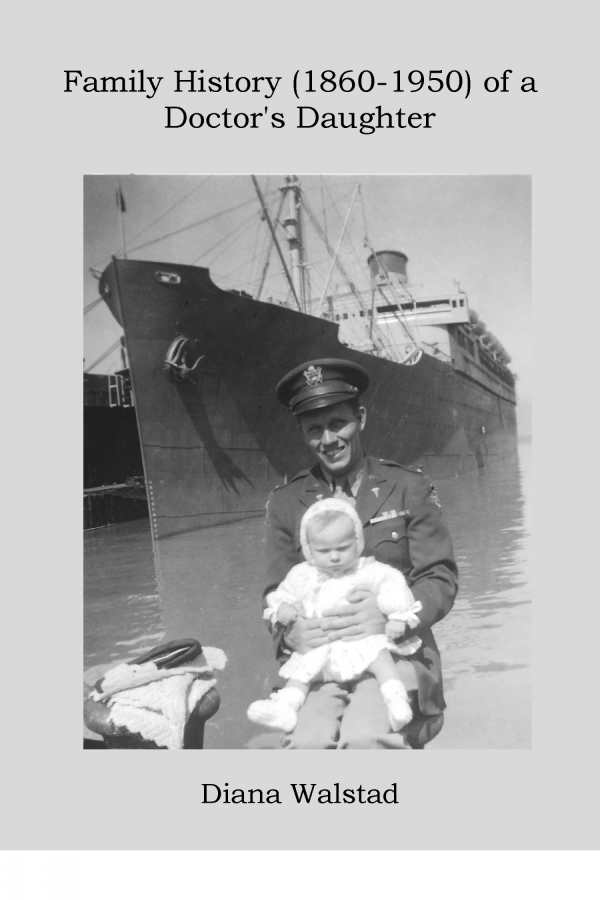

Walstad includes charts, maps, footnotes, photos, and well-researched asides, giving detailed histories of related events. A picture emerges of the northern Midwest in the late nineteenth century, with its sod houses and itinerant preachers, contrasted later with California in the early twentieth century, with its prosperity and sunshine.

Walstad organizes events by time periods, often interrupting the story to serve the structure, rather than altering the structure to serve the story. For example, the first chapter covers 1860-1890, while the second goes back to 1870 and then forward to 1900. In the first chapter, great-grandfather John Walstad’s immigration is followed by a slight leap to great-grandmother Maren, then to maternal great-grandparents and so on, with corresponding historical information. Chapter two includes more names, leaps, and history. A family tree at the beginning of the book is handy for keeping track, but it’s still difficult to follow who’s who, and this becomes the main problem with the book.

Themes arise: a lack of mother-daughter bonding repeats over the generations; tuberculosis plagues the family; children whose biological parents cannot or will not keep them are taken in and adopted by other, related families who keep them financially but not lovingly. Some of these stories are compelling, like when great-grandfather Lambert (or is it grandfather Lambert Jr.?) feels he must give his baby daughter to another family.

The book might have benefited from more attention to the universality of its characters’ lives: What did they have in common with others of their time? How can a modern reader connect with them? How are they like everyone else? The author almost achieves this through quotations and historical information—a recognition, a face in a photo to bring other faces to mind. But as the book jumps from relative to relative and story to story, it suffers from a lack of cohesion, coming to an abrupt end without a satisfying conclusion.

The author’s style is straightforward and competent. Excerpts from letters and conversations help make ancestral voices clear, and students of the period will be intrigued by the history. But Family History (1860–1950) of a Doctor’s Daughter will likely be most interesting to the author’s family and not general readerships.

Reviewed by

Petrea Burchard

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.