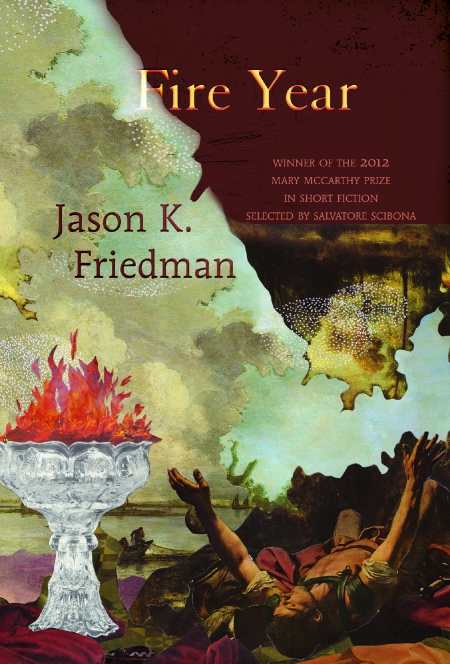

Fire Year

Post-modern exploration of the Jewish experience in the American South is shaped by defined, sympathetic characters and ironic humor.

In a collection of seven pieces of literary fiction, winner of the 2012 Mary McCarthy Prize, Jason K. Friedman, confronts love and religion, family and sexual identity, faith secular and holy, and humor wry and hopeful, in an exploration of the Jewish experience in the American South.

The collection opens with “Blue,” in which an awkward boy at his bar mitzvah takes his first stumbling steps toward adult awareness. After immersing himself in the Torah as part of the ceremony, he confronts the mundane. “Reunion” follows. A hip and edgy New Yorker reluctantly returns home to Savannah for his twenty-fifth high school reunion—there bemused and then seduced by a former classmate, “the rich kid who played football and baseball,” only to comprehend that his heritage will always set him apart. Set in 1927, “All the World’s a Field” finds Miriam confronted by her sons over her attachment to a milk cow, the animal perhaps symbolic of her confusion over their quick assimilation. A crisis comes when the cow is sold so that the family can move. “The Cantor’s Miracles” focuses on a deception provoked by resentment. The cantor, “paid like a waiter, the management expecting him to hustle for tips,” resents that he must worry over the congregation’s largesse as he trains their children. In “The Golem,” Artie goes to work for Blaustein in an auto repair shop. Artie, apparently brain-damaged after being assaulted by Irish teenagers when he was a boy, has a savant-like talent for supplying Blaustein’s shop with junkyard parts, something that Blaustein, a caricature of the tight-fisted, greedy businessman, both resents and values.

Friedman writes with an air of post-modern irony yet remains fully sympathetic to the characters who people his stories as they fumble toward irresolution. The first five stories are set in Savannah or its environs, but the final two, more complex in theme, move away from the low country.

“There’s Hope for Us All” recounts the story of Jonathan Weitz, recent graduate of Yale, as he flounders in his first job at a gallery in Atlanta. Through the naive insight of his lover, Ali, Weitz develops a startlingly interpretation of an obscure sixteenth century portrait, turning upside down the work of an imminent Italian scholar and, ultimately, revealing the fragility of his love affair. The title story concludes the collection, its Eastern Europe setting, “a region of lakes, banked with soft carpets of grass in summer, crystalline ice in winter,” ruled by far away St. Petersburg. There Zev, son of Reb Aryeh, is compressed into silence by the superstitions of scholarly numerology. All that is familiar collapses when his older brother denies his faith. Friedman writes here with an undercurrent of homoeroticism, until Zev, confronted by his father to turn passion into holiness, finally replies, “It doesn’t work.”

In this Isaac Bashevis Singer-like take on the Jewish experience in the American South, with humor set against despair, Friedman writes with a gift for language, employing words and phrases quietly. The characters are real and diamond-sharp, but observing from the outside, always through the lens of Jewish culture, oft times amplified by sexual identity.

Reviewed by

Gary Presley

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.