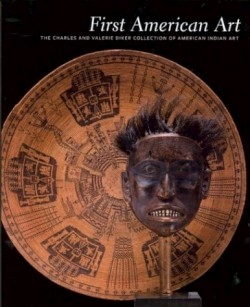

First American Art

The Charles and Valerie Diker Collection of American Indian Art

Currently on display at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in New York City is an exhibit of the Diker Collection of Native American art. The Dikers also have an extensive collection of modern and contemporary art in their home, and it was there that the curators of this exhibit, Native and non-Native scholars alike, came together to discuss the meanings of Native art.

Inspired by the unique juxtapositioning before them of historical Indian art with modern art-an Acoma olla placed on a table beneath two huge Jean Dubuffets and a colorful Calder mobile, for instance-the curators organized their discussion around seven aesthetic principles common to both: idea, emotion, intimacy, movement, integrity, vocabulary, and composition.

Bernstein is assistant director for Cultural Resources and McMaster (Plains Cree) is deputy assistant director for Cultural Resources, both at the Museum. They, along with Kuspit, professor of art history and philosophy at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, and Dubin, a scholar and lecturer, contributed several challenging and illuminating essays to the beautifully illustrated catalogue.

Bernstein and McMaster dissect many objects in the exhibit in terms of these seven principles, and by so doing, validate them not only as cultural artifacts, but as true works of art. The creator of an exquisite Apache basket, dated approximately 1880 and woven of willow and yucca root, clearly thought about his composition of alternating bands of herders, animals, and perfectly repeated geometric shapes before beginning his piece. The iconography had been utilized by many before him, ensuring the basket’s integrity, and he knew that the meaning of the symbols he used-their tribal vocabulary-would be recognized for generations to come.

The exhibit’s aim is to bring such objects from the natural history museum to the art museum-just as the Dikers have done so eloquently in their own home-a move that changes the viewer’s perceptions. The authors feel that the artist’s times and surroundings should not be ignored, but moved into the background, for to be considered art (and not artifact) an object must be timeless. “When meanings are lost,” the authors explain, “then baskets become objects,” and not art.

Encapsulating the exhibit’s theme in his essay “The Spiritual Import of Native American Aesthetics,” Kuspit writes, “I want to de-emphasize the cultural, emphasize the aesthetic aspect-the sensuous elegance and power, which invariably signify spiritual depth and complexity-of Native American art.” With this exhibit and its superb catalogue, the National Museum of the American Indian is constructing a “new paradigm,” which allows Native art to be recognized as art, and which allows it to “engage in a dialogue” with other art forms-and invites the viewer to do so as well.

Reviewed by

Deborah Donovan

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.