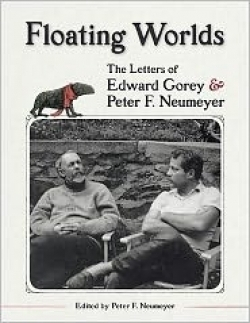

Floating Worlds

The Letters of Edward Gorey & Peter F. Neumeyer

Fans of the prolific author/illustrator Edward Gorey will delight in Floating Worlds: The Letters of Edward Gorey & Peter F. Neumeyer, which chronicles the personal correspondence between the pair as they collaborated on three children’s books.

But even those uninitiated to the macabre and fanciful world of Gorey (never seen the Masterpiece Theater introduction on PBS?) will revel in the tome as well—it’s sort of a Griffin & Sabine for the literary set, with flashes of Gorey’s remarkable wit, self-deprecating humor, streaks of melancholia, and most of all—his brilliance—shining throughout.

The letters—never before seen—flew between the pair at a fair clip for a year, from September 1968 to October 1969, while Gorey was illustrating three books Neumeyer had written: Donald and the … , Donald Has a Difficulty and Why We Have Day and Night. At the time, Gorey (“Ted” to his friends) was writing and illustrating books while living in Cape Cod and New York City; Neumeyer was a professor, first at Harvard and then at SUNY Stony Brook.

The book is filled with pictures of beautifully illustrated envelopes, handwritten postcards, and typewritten notes that cover everything from the books to the men’s shared love of literature, philosophy, and art. But they are more than just creative affairs—readers get to witness the birth of a platonic friendship in these honest, emotional letters tugging at the heart. They will make many a reader long to have such a deep, intellectual, passionate, and creative relationship with someone.

Neumeyer alludes to their bond in a letter from September 1968, writing “I feel I have found in some measure my artistic counterpart.” Gorey writes the same in a letter from October 1968: “I feel in a way as if I had known you always.”

Each peek into one of Gorey’s illustrated envelopes reveals something new—a baby dangling a rainbow-colored dragon by the tail, perhaps, or a four-legged critter (in this case a “stoej-gnph”) merrily roller skating. In one letter he discusses reading various translations of the work of Jorge Luis Borges; in another he writes of his fondness for Barbarella. His predilection for cooking turns up as well, as do his artistic sensibilities: after quarreling with their editor about one of the books, Gorey writes, “I am angry. I am enraged. I want to beat Harry Stanton (the editor) about the head with a pewter mug.”

Although one wonders what happened to the friendship once their correspondence fell off, the book is a deeply satisfying read. Gorey fans will gain a fascinating insight into the day-to-day life and work habits of the prolific author (he penned more than one hundred books); literature fans will gain hundreds of new titles to peruse (both men were avid readers)’ and fans of fine art will wonder at the many intricate cross-hatched illustrations inside, much like Neumeyer did in early October 1968: “Your envelopes are making a beautiful exhibit,” he writes. “I keep thinking they will lend themselves to something—though I can’t imagine what.”

Reviewed by

Dana Rae Laverty

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.