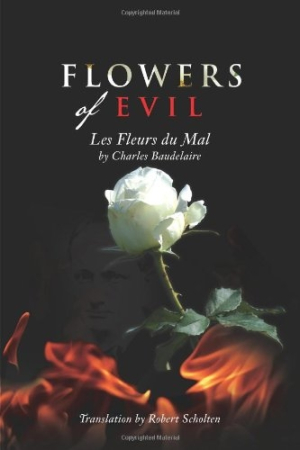

Flowers of Evil

Les Fleurs du Mal

This translation of Baudelaire’s masterpiece is a successful gateway to the French poet’s dark, affecting work.

Charles Baudelaire has a special place in the history of poetry as perhaps the first poet to fully embrace the darker side of life in his work. Robert Scholten offers his translation of all 160 of Baudelaire’s poems in the volume Flowers of Evil.

Translating Baudelaire is something of a cottage industry in the world of poetry, with many scholars and poets making attempts over the years. With the poems originally written in Baudelaire’s native French, translators usually fall into two camps: those who place Baudelaire’s poetic meaning ahead of his form and technique and those who are willing to sacrifice a bit of poetic meaning, changing it as necessary in order to better fit Baudelaire’s rhyme and syllable patterns into English.

Scholten’s approach is of the latter kind, and he does an admirable job, given his self-imposed restraints: preserving Baudelaire’s rhyme and meter patterns as much as possible while offering interpretations that are not consciously influenced by any of the previously published translations.

As an example of the differences in existing translations, one can examine the third stanza of the introductory poem “To The Reader.” As translated by Carol Clark, whose efforts to preserve meaning went so far as to abandon rhyme and form, it reads, “On the pillow of evil it is thrice-great Satan who keeps our bewitched spirit long slumbering, and the rich metal of our will-power is all turned to vapour by that master of chemistry.”

Wallace Fowlie’s 1964 translation, also discarding Baudelaire’s rhymes, reads, “On the pillow of evil it is Thrice-Great Satan / Who endlessly rocks our bewitched mind, / And the rich metal of our will / Is vaporized by that wise chemist.”

Walter Martin’s 2006 translation keeps Baudelaire’s rhyme scheme but converts to ten-syllable lines: “Great Satan lullabies our spellbound hearts / And rocks us in his cunning cradle, till / The pliant precious metal of our will / Is vapourized by his hermetic arts.”

Scholten translates this stanza as follows: “On the pillow of evil it is Satan, that lizzard, / Who rocks and enchants our spirit, until / The most precious metal of our glorious will / Is turned into vapor by that dextrous wizard.”

It is impossible not to lose something in the translation from French to English, and it will fall to the taste of individual readers as to which sort of translation they prefer, but Scholten’s effort is noble and successful. He manages to avoid rhyme’s tendency to juvenilize its content, a difficult task even with Baudelaire’s clearly adult mindset.

Scholten is something of a latecomer to formal study of Baudelaire, having served as professor of geology at Pennsylvania State University, among other jobs. Taking up the translation of Baudelaire’s poems in retirement, the project grew to a ten-year endeavor, finally resulting in this book.

The volume is ideally designed, with opposing pages showing the original French and the English translation. Scholten’s translation is worth reading for fans of Baudelaire’s work; it might also make an ideal introduction for those who have never read the French poet’s dark and affecting poems.

Reviewed by

Peter Dabbene

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.