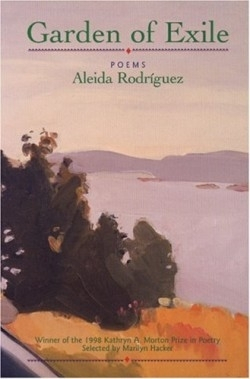

Garden of Exile

For one whose bread and butter is earned with words, Rodriguez practices a determined suspicion about the power they posses. In her poem “Why I would rather be a Painter,” she unapologetically states that “Dictators dwell in palaces of words while peasants swill the backwash of those lies,” exposing the consequence of certain words in the terms of people’s real lives. It also appears that in choosing to write poems, Rodriguez has consciously rebelled against the misuse of language and has instead reinvented its function for herself.

Having left Cuba at the age of nine, Rodriguez’s evolution as a writer has been directly influenced by the dubious circumstances of her emigration and subsequent alienation from the Spanish language. Garden of Exile, which won the 1998 Kathryn A. Morton Prize for Poetry, is a book about reconciling this and other falls from innocence and also about the desire for fulfillment, especially with regard to lesbian love. Throughout the collection there is a preoccupation with finding the appropriate means to record the motifs and rituals of place and experience.

Rodriguez employs rigorous, well-crafted images without self-consciousness or hesitation. Language is treated as three-dimensional: something, which can be handled and manipulated. The process of the poem’s making is demonstrated in the candid layering and accumulation of information within the poem.

By virtue of her aesthetic and utilitarian concerns, saturated sentences catapult the reader into a heightened awareness of the world: “the overripe sapotes fall / with a squishy thud; where the lemon, pointillistically studded / with fruit, glows like a celebration; where the loquat drops / yellow vowels and the scrub jays nesting in the lime / chisel them noisily with their hard black beaks.”

Nostalgia for the homeland, and “childhood’s cerulean sky, fat with meringue clouds” is a predictable consequence of emigration. This tendency, however, also inspires an articulate skepticism elsewhere. Her occasionally conversational tone is one means of tempering this, as if to guard against the sloppiness of more elaborate and romantic diction. In one poem, the narrator is a caller on her answering machine; in another, she is humbled in the presence of a senior Chilean novelist wondering “was my outfit too coordinated?”

In the section entitled Cuentos de Cuba, Rodriguez travels a middle path, writing in both of her languages: “mi abuela” is not renamed, nor are the “brujas or locos” whom she imagines lived along the beach of her youth. These words that survive without translation do so as if to demand perfect accuracy from the author, “There is no way to pull the harsh tongue / from my mouth.” Despite the fracturing this may cause in the poet, they are in fact beautiful.

Reviewed by

Holly Wren Spaulding

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.