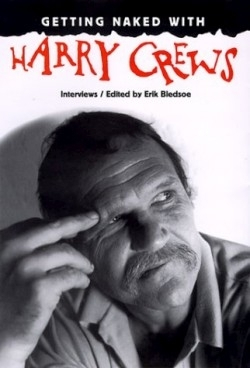

Getting Naked With Harry Crews

“If you’re gonna write, for God in heaven’s sake try to get naked,” insists author Harry Crews. “Try to write the truth. Try to get underneath all the sham, all the excuses, all the lies that you’ve been told.” Editor Bledsoe, an instructor of English and American studies at the University of Tennessee, put together and edited this collection of twenty-six published and unpublished interviews, including one of his own, that collectively cover a period of twenty-five years. During an only slightly longer period of time, Crews, now sixty-four, has published at least twelve novels, an autobiography, screenplays and columns and articles for magazines like Esquire and Playboy.

It would seem a bit pointless to argue that unless the subject at hand is the man himself a clothed man can reveal truth as ably as a naked one. For one thing, this book is about the man himself. For another, Crews is a man who has approached life without a safety net. Crews doesn’t observe the human condition, he plunges into it. If Harry Crews is naked, you can bet the emperor has no clothes. Growing up in a tenant farm family in Georgia, he survived an alcoholic stepfather who punctuated his brutal rages with random shotgun blasts about the house. He survived a plunge into vat of boiling water intended for dead pigs. He survived a bout of infantile paralysis. As an adult he has survived drug binges, drunken scrapes and pool hall brawls that left him jailed, broken and bleeding.

“If you can’t play with pain, you can’t play,” he told interviewer Hank Nuwer, who titled his interview “The Writer Who Plays With Pain.” A moment earlier Crews had differentiated himself from the literature professors at the University of Florida: “They ain’t seen blood, and all their bones are intact. They see a little blood and they think the game’s over.”

Bledsoe, however, hopes this collection will provide balance to the public legend of Crews as a macho drunkard, out on the edge and flirting with self-destruction. “Certainly, he is at times revealed as boisterous, abrasive and self-destructive, but we also see a Crews who is thoughtful and concerned, both on a social and human level, a man who can be incredibly tender and charming,? Bledsoe writes.

The book does provide such glimpses, as in Crews mulling over the nature of religion. While surely not alone in seeing himself as a believer with nothing to believe in, he is perhaps more than commonly devout in believing “church is really good for one reason: it is a place to go and sit down and contemplate the inadequacies of your own heart .”

Perhaps of more interest are the things Crews says about the creative process and the craft of writing. His stories involve grotesque events and characters. Crews detests automobiles, and his novel “Car” a man eats one, piece by piece. A frequent Crews device—some would say his signature device—is to people his novels with so-called freaks: a man with withered legs who walks on his hands, a man who weighs 600 pounds, any number of midgets and the founder of a soap company who gives inspirational speeches to his minions through a harelip.

The creation of such stories and characters is not a particularly conscious process, Crews tells his interviewers. He talks of sitting down to begin a story and groping in the dark until the characters and their circumstances begin to form. Then, during extensive revisions and rewrites, he strives to shape his stories along the clean, narrative lines he very much admires in the work of Graham Greene.

Harry Crews has lived hard to acquire the raw material, the darkness in which he gropes for stories, and he has worked hard at mastering the craft of telling them. He tells interviewers he is deeply suspicious of both postmodernism and science fiction. Blood and bones are what are important, he says.

“See, I believe all of the best fiction is about the same thing,” he says in a 1992 interview at Memphis State University. “It’s about somebody trying to do the best he can with what he’s got. That’s all “ the best he can with what he’s got “ sometimes nobly, sometimes ignobly.”

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.