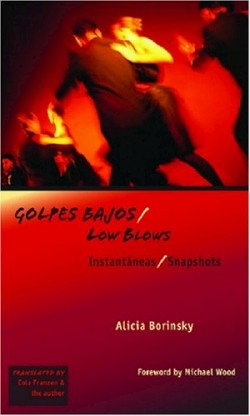

Golpes bajos / Low Blows

Instantaneas / Snapshots

There’s something about mocking tragic loss that allows the reader to hate the observer even more than what’s being observed. A first reading of Golpes Bajos might fall on eyes as critical as those the poet turns on her own native Argentine culture. On the other hand, some who have turned away in disgust from the awful truth might be enlightened to discover there are better ways than armed reprisals to raise the consciousness of an indifferent public.

This voice arises on the wings of a scandalous irony. Political irony there is aplenty here, fired by contempt for the lack of intelligence underlying social unconcern, but it is in the arena of the more personal that a reporter can land the blows that really sting. Perhaps the only way an observer of particular sensibility can tolerate the abominations of a disintegrating society is to turn the gaze on the petty cruelties of the salon—the surgical glance, the ironic understatement, the fake courtesy.

Is this poet truly as heartless as her brutally real portrayals of the shocking tackiness of human unconsciousness suggest? The answer lies in those interstices where a shred of compassion creeps in, as though in spite of itself.

An example is a scene where a woman watches (with a casual contempt) her married lover pretend to ignore her as he rushes for the train home “although we didn’t go through half the excellent bottles of wine I got for us at a discount …” One can only wonder if the spiteful note she’s written to the wife is justified by the lover-cum-erring husband’s obviously dehumanizing treatment of her.

A whole poem (“Mismatch”) summarizes in four lines a marriage in which two people might have had something significant to say to one another and never said a word: “In that house a woman is standing before the window weeping while the man who’d been silent for three months, four days, and five minutes sings an aria that she can’t understand; although she’s perfected her Italian to the nth degree, he only likes to sing in German.”

Alicia Borinsky is professor of Latin American and Comparative Literature and director of the Writing in the Americas Program at Boston University. Working together with a familiar translator the poet herself advises in her preface that “a great part of the pleasure of bilingual editions consists in the counterpoint , , , that lies between languages, the thrill of finding how the same effects may be created in a language with very different cultural associations.” This extra benefit is even more welcome when it is, as in this collection, consciously planned.

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.