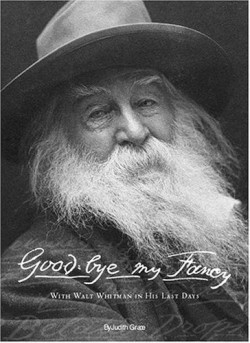

Good-bye My Fancy

With Walt Whitman in His Last Days

In the introduction, Whitman scholar Robert MacIssac describes this book as “a dialogue of truth.” Less metaphorically, it is a three-part, two-person dramatization. The author is a poet and editor who founded the literary magazine, Lyra, and has written more than thirty short plays, which have been performed in New York and California. Here, she writes of the friendship between Whitman and Horace Traubel in the last sixteen months of the great gray poet’s life.

Traubel was only a teenager when he first met Whitman in the 1870s, when the poet was in his fifties. Whitman became a mentor to the young would-be writer, and their friendship lasted until Whitman’s death in 1892. Afterwards, Traubel was Whitman’s literary executor and strongest defender. During the final four years of Whitman’s life, Traubel played Boswell to Whitman’s Johnson, visiting him almost daily and dutifully transcribing their conversations every night. These notes became the basis for Traubel’s nine-volume biography, With Walt Whitman in Camden.

That massive collection is Grace’s sourcebook for her much briefer dramatization. The conversations between the characters are often verbatim as recounted by Traubel. Grace takes artistic license, of course, to create a dramatic structure for her own work.

In the three scenes of the drama, Whitman alternates between a certain self-pity and self-assuredness. During his low spots, Whitman reminisces with his friend about the horrors of the Civil War, the death of Lincoln, and the harshness of his critics. “The Press,” he laments, “has been the meanest, most malignant, most lying—a searcher after hidden blackness, a suspicioner of motives, a pecker at the foibles of humanity—a sort of journalistic imp of Beelzebub!”

The second scene finds Whitman in a much better mood. It is his birthday, and he is surrounded by gifts and telegrams from well-wishers. In this scene he sounds like the confident narrator of Leaves of Grass: “I never did feel as though the discussion of religion should be left to the priests; it never seemed to me safe in their hands. I am not convinced by the formal martyrdoms alone; I see martyrdoms wherever I go. The common heroisms of life are anyhow the real heroisms.”

The play ends with Whitman on his deathbed, weak but accepting the next stage of his journey through the cosmos. “I glory in the surrender,” he says, “have no regrets, have nothing to recall.”

The strength of Good-bye My Fancy is its language, not surprising since much of it was first uttered by America’s greatest poet. The book’s weakness is its brevity. Readers who stumble upon the dramatization without prior knowledge and understanding of the special friendship between the two men will not likely get a sense of it from this work. For more knowledgeable fans of Whitman, the book is a nice, but not vital, addition to the collection.

Reviewed by

Erik Bledsoe

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.