Grandmama's Pride

Last year the United States recognized the fiftieth anniversary of the landmark Supreme Court decision, “Brown vs. the Topeka Board of Education,” a decision that declared segregation in U.S. schools unconstitutional. In academic arenas and other circles across the nation, debates exist around the decision’s legacy. Wounds were reopened and harsh memories, once buried, were resurrected.

This book is based on the author’s recollection of family trips South, where racial harmony has been, and in some locales, continues to be, tenuous. An accomplished writer of poetry and short stories for adults, Birtha works with an adoption agency and writes extensively about adoption procedures. This is her first book for children.

It is the summer of 1956—two years after “Brown” and just one year after Claudette Colvin and Rosa Parks refused to give their seats on public buses to whites—when Sarah Marie’s family take their annual trip “down south.” As the trip begins, relatives try to protect the children by making up excuses for the inferior treatment of Blacks, rather than explaining the Jim Crow laws that exist in the South. “The back seat is the best seat on the bus,” Mama claims, while Grandmama says, “God gave us each two good strong legs for walking.” Today’s readers might easily misinterpret this type of pride, but a knowledgeable narrator reflecting on the experience explains that at the time she did not know that Grandmama walked because her “pride was too tall to fit in the back of the bus.”

It is literacy acquisition that informs the narrator, demolishing her innocence and changing her worldview forever. Aunt Maria teaches her to read, enabling her to make sense of the “whites only” and “colored” signs above public facilities. When asked, Grandmama tells Sarah Marie the truth about segregation. This new knowledge is both freeing and restrictive. Suddenly she longs to return home “far away from unfair signs and laws.” At the bus station, she adopts Grandmama’s and Mama’s coping mechanism, telling Sister, “You don’t want to sit on those public benches … You don’t know who’s been sitting there.”

At home, Sarah Marie becomes a voracious reader, keeping up with the Civil Rights Movement until the summer of 1957, when she returns to the South to find that they can “try something different” like riding in the front of the bus, ordering at lunch counters, and sitting down in waiting rooms. However, an Author’s Note explains that in 1957 the South was still largely segregated.

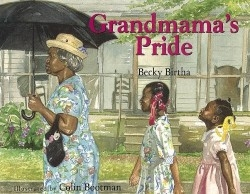

The illustrator is a Coretta Scott King Honor Award recipient for Almost to Freedom. Here, his depictions of the characters’ emotions reveal pride, love, and hope. The setting could spur discussions in classrooms about events that occurred during the fifties and sixties, only four years from “freedom summer,” a period when pride led to action.

Reviewed by

Kaavonia Hinton

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.