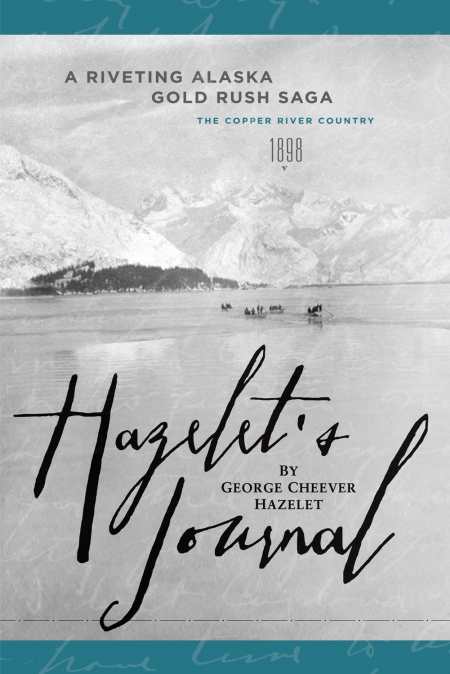

Hazelet's Journal

A Riveting Alaska Gold Rush Saga

- 2012 INDIES Finalist

- Finalist, Autobiography & Memoir (Adult Nonfiction)

- 2012 INDIES Finalist

- Finalist, History (Adult Nonfiction)

Step aside, Jack London, and make room at the bar for George Cheever Hazelet. John Clark’s marvelous edit of the journals his great-grandfather penned during the Alaskan Gold Rush are every bit as exciting and authentic as what the author of White Fang and The Call of the Wild wrote. Contemporary in experience and outlook, George Cheever Hazelet should have been the chronicler of the Klondike. He may yet become that.

Beautifully written and lightly edited in order to maintain the pace and emotion of the entries—some hurried, some pensive—Hazelet’s Journal is primary-source history at its finest. This is not some musty pile of scribblings left to gather dust but a vibrant document into which generations of the family have breathed life. Clark, a printer by profession, has completed a task begun by his great-grandfather on a train leaving his Midwest home in 1898, and he has done so with a light yet deft hand.

Clark’s recruitment of Douglas Keeney—a noted historian, author, and a founder of the Military Channel—to present the prologue adds both gravitas and an independent point of view to introduce the narrative. Clark resisted the urge to “clean up” the journals, noting with unnecessary apology his “editorial decision to leave the journal entries, in almost every instance, exactly as my great-grandfather wrote them.”

Not that Hazelet’s work needs much correction. This was no schoolboy adventurer. Hazelet was a college graduate, businessman, husband, father of two, and school principal before heading off to seek his fortune in the Alaskan wilderness at age thirty-seven. His was a journey of desperate necessity, an attempt to recoup losses sustained in the depression of the late 1890s and to “be successful for my family’s sake.”

While he admired the beauty of the “wonderful country,” Hazelet did not want to be in Alaska. “If we could make a find we would at once pull out for home and happiness,” he writes. His journals are as much about longing for family as they are about the exploration of the wilderness, an adventure which he found so hard and wearying that “at times I feel like making a kicking machine and turning it loose on the seat of my pants.”

The book is lavishly illustrated with well over a hundred photographs. Hazelet, his comrades, their camps and canoes, pack trains, and digs are the subjects of many of these images, which in themselves chronicle the Klondike Gold Rush of 1898-1902. There are also many amazing and beautiful photos of glaciers, mountain trails, and winding, rapid rivers so dangerous that their twists and turns are still known as the Devil’s Elbow and Hell Gate.

This is no staid diary. There are forest fires, floods, gunplay, and many other death-defying episodes. There is little glory here other than that of nature; as Hazelet notes, “the work is simply killing and that is all there is to it.” This is no mere metaphor, however, as Hazelet, in his best Jack Londonesque voice, makes note of more than one man who “came into this wild country to find his fortune and found his death.”

Reviewed by

Mark McLaughlin

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.