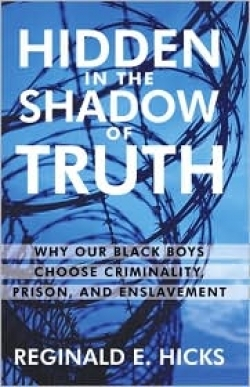

Hidden in the Shadow of Truth

Why Our Black Boys Choose Criminality, Prison, and Enslavement

It was 1992, not 1962. It was at the State University of New York, Albany, campus, not George Wallace’s University of Alabama. But still, young Reginald E. Hicks overheard a group of white students discussing what they called “the black problem”—and they weren’t referring to racism, poverty, or the residual oppression from more than two centuries of the chattel slavery. It was an ugly conversation filled with stereotypes and ending with the racist assertion that prison was, for African Americans, a paradise. That stinging, stunning moment stuck with the author and became one of the reasons he wrote this book.

Hicks, who has spent fifteen years teaching high school sociology and geography, worked in group homes and has master’s degrees in theology, African American studies, and secondary education. He has been pondering, researching, and struggling with the fact of falling graduation rates and high incarceration rates in the Black community for years.

Hicks has built a powerful argument about the difficulties faced by African American boys by thoroughly analyzing numerous factors that contribute to low achievement, such as a lack of positive male influences at home, a school system that has few Black male teachers as role models and lowered expectations for Black male students, the social conditions of slavery that carried over into the penal system, negative influences from peer groups that emphasize machismo and glorify prison life, and mass media that uses racial stereotypes for profit and politics. “But,” Hicks writes, “human beings are not automatons that can be programmed for inevitable success or inevitable failure.” Choices made by a certain demographic of young Black men are often the cause of negative outcomes.

The author contends that for the young men who wind up in prison, choice, and not overwhelming circumstance, is a real and addressable problem, as important to the success or failure of an individual as outside influences.

Some excellent examples of potential role models are provided, men and women who have not succumbed to seemingly insurmountable obstacles, like Jesse Jackson, Oprah Winfrey, Tyler Perry, Maya Angelou, and Malcolm X. These individuals offer hope for a break from what statistically and empirically seems like a long slide from the uplifting militancy of the Civil Rights struggle to today’s high rates of failure, incarceration, and recidivism for young Black men. Hicks writes, “people emerging from the bleakest circumstances show that even in the face of what can certainly be categorized as hopelessness and despair, choice—as difficult as it may be—is always a factor.”

This book is powerfully argued, rigorously researched, and challenging for readers both inside and outside the African American community. It deserves to be read and should have been published by a university press. No functioning free society can afford the squander the energy and creative resources that young African American boys represent.

Reviewed by

Deirdre Sinnott

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.