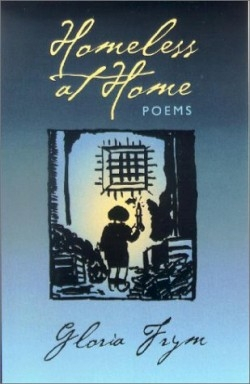

Homeless at Home

Combine the brevity of William Carlos Williams with the poetic leaps of Emily Dickinson, add a tough, yet passionate voice, and the result could be close to Frym’s fourth poetry collection, Homeless at Home.

From the Dickinson poem that prefaces her book, Frym takes her title and initiates a correspondence with her deceased father in fifty-four letters. She attributes the premise of her project to poet Jack Spicer, who insists that “poetry is an argument between the dead and the living.”

The letters are not so much the personal history of the pair, but rather the history of the world and the ideas that the two generations did—or did not— share before her father’s demise.

Sprinkled with references to Emily Dickinson and a few loose renderings of the sonnet form, the collection tackles both global injustice and philosophical conundrums with uncomplicated language, music, and structure. “We washed our hands after reading the news / but we were never innocent bystanders. / Long ago, we pulled the plug / and the alarm continued to ring.”

The staccato, often subjectless lines accumulate, however, into complex ideas of what it means to live, work, and die in an imperfect world. At times, the simplicity of the lines errs on the side of disjointed abstraction, sentimentality, or triteness. In one ten-lined poem, the speaker concludes, “I would like to write a poem / that equals / The Snack Bar at Auschwitz,” too easily dismissing that potentially more thoughtful poem.

Though the collection occasionally falters, Homeless at Home swells with the wisdom of the world and the language used to understand it. At the same time that she describes current and past events to her father, Frym engages him in a poetic education, of sorts, breaking down the constructs of language that most people take for granted. “P.S.,” she writes at the end of one of the collection’s most personal poems about alcoholism and economic hardship: “This is how narrative actually grows, adding a few words at a / time. A mark now a bump then a chunk. You just never noticed.”

This is, perhaps, the most enduring gift of Frym’s work: it stands up simply, firmly, and makes the reader look a little bit harder at what he or she may otherwise blindly accept.

Reviewed by

Jessica Belle Smith

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.