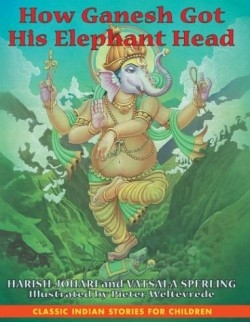

How Ganesh Got His Elephant Head

Most American children’s exposure to fairy tales or mythology is limited to those with European or perhaps Greco-Roman origins. The wonderful, non-sanitized versions have wicked characters, battles, hulking giants, brave beasts, and children. The best ones may be scary and even teach a lesson.

This is a delicious, classic story, from India, about a small boy who becomes the god to whom people take their troubles. He is conceived by Parvati, a mother goddess married to Shiva, God of Destruction. Parvati is annoyed by her husband’s rude interruptions of her bath (so typical of a God of Destruction). While Shiva is away, she makes a little figure to guard her door, a boy made out of sandalwood paste. She breathes life into him and when he asks what he can do for her, she gives him a wand to hold as he stands watch.

Shiva returns, and is surprised to find a child who won’t let him near his wife. Determined to interrupt the bath, Shiva begins a series of assaults. He brings a band of ruffians and a bull to attack, but the powerful wand works its magic.

Like many domestic conflicts, the situation does not remain within the family. A sage traveling between heaven and earth and the netherworlds reports the situation to gods Brahma and Vishnu. Alarmed that the boy might become too powerful, they rush to help Shiva. The massive forces against the boy include an army and a thousand gathering storms. Parvati, now out of the bath, joins the fight.

The turning point comes when Vishnu, with the unfair advantage of having four arms, pulls out a razor-sharp weapon, and Shiva cuts the fat-bellied child’s head off while Parvati watches in horror. “Her son had acted with unquestioning devotion,” reads the story, “defying the most powerful gods to protect her privacy.” Her anguish turns to anger.

The only thing that will placate her, however, is to have her son returned to life. Vishnu agrees to find a suitable head—that of a sacrificial baby elephant. There is a tender, but sad, moment when the mother elephant gives up her child so that the boy may live. Shiva, surprisingly, adopts the odd-looking child, named Ganesh.

While the major gods have been distracted, things have gone bad on earth. It becomes little Ganesh’s job to “help people on Earth whenever they are in trouble or in need.”

The drama of the story is illustrated in an ancient art form of wash paintings, as elegant as illuminated manuscripts, or as shimmery as silk saris with threads of gold. This technique was developed by the late author and his students, including this illustrator, who has provided art for two other books by Johari, and has been recognized by the Dutch government as a master artist. The wash technique infuses the figures with light, giving them a spiritual quality beyond the aura around their heads. The stylized figures evoke artwork found in Indian temples and caves.

The process of creating wash paintings using watercolor and tempera is described in the backmatter, along with notes to parents and teachers about how to interpret the story and discuss it. Children will be especially interested in the characters’ hand positions (mudras), symbols of emotion and communication.

Johari, aside from being a spiritual leader, composer, painter, sculptor, scholar, and teacher of Indian traditions, was the author of several books for Western readers, including Little Krishna, Chakras, and the Monkeys and the Mango Tree. Sperling, a native of India, studied Brahmin religious rites, is fluent in Sanskrit, and co-wrote A Marriage Made in Heaven, about her marriage to a Jewish American publisher.

Their spirited tale has a lot of juicy violence, which is the fabric of mythology, the drama of Sophocles (remember Oedipus), Biblical stories (David and Goliath), and even Hansel and Gretel or Little Red Riding Hood.

While the story of Ganesh may have young children gripping their security blankets, it, like scary Western fairy tales, offers lessons. Most strikingly, the stalwart, victimized boy, when he is transformed into a god, becomes a problem-solver, not a vengeance-seeker. The excitement of the tale should lead to good discussions about forgiveness, getting along in families, and, perhaps, modern bathroom privacy. There is nothing like a good lock.

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.