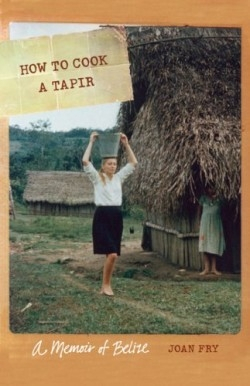

How to Cook a Tapir

A Memoir of Belize

First, it helps to know what one actually is. Tapirs are not native to the sheltered suburban enclave of Verona, New Jersey, where Fry grew up; the most exotic animal she was likely to encounter was Fluffy, the neighborhood cat. But when you’re a young bride in 1962 and your new husband is an anthropology student intent on spending the first year of your marriage studying the native Kekchi and Maya tribes in British Honduras (now Belize), you have no choice but to go along for the ride.

And what a ride it was. Hauling water in leaky buckets from a distant river, sleeping fitfully in an under-sized hammock, and checking for tarantulas before putting on her shoes, Fry’s new life in an isolated jungle village was an intimidating yet intriguing mix of primitive accommodations and perplexing cultural mores. As the only white woman for miles around, Fry’s race, privileged upbringing, and youthful naïveté made her both an object of curiosity and a target for derision.

With very few exceptions, in most cultures the preparation of food is considered a woman’s occupation. For Fry, the job included a few occupational hazards, thanks to a shallow pit and some strategically placed rocks. Never mind the tapir—even a simple cornmeal-and-water tortilla was beyond her culinary ken. At one point, it seemed the local diet would do her in. “Chicken feet in tamales? Soup made with rodents the size of dogs? How did I know the Maya didn’t make dog soup?”

She didn’t, and it wouldn’t have much mattered if Fido did turn up in the escabeche. As her husband, Aaron, was fond of reminding her, her role was to adapt and assimilate; to fit in. She was tall, fair, hopelessly blond. Her neighbors were small, dark, and the women rarely wore any clothes from the waist up. How, exactly, was this supposed to happen?

It happened when Fry was hired by the regional Catholic church to provide the village children with a basic education. A college dropout with no teaching experience to her credit, Fry was as woefully unprepared for this new wrinkle as she had been for every other aspect of jungle life: “I didn’t have a formal lesson plan. I didn’t have textbooks. I didn’t have anything except stage fright and a respectful group of kids who seemed excited to be here. It was years before I appreciated the fact that their atti-tude might have been more important than mine.”

Attitude was something Fry struggled daily to improve. Hampered by an appalling lack of privacy, Fry’s every move provided an endless source of fascination. Though she eventually did come to harbor a deep and abiding respect for the people of the village, getting used to her living conditions took considerably more time. “Living in a bush house in the middle of the jungle,” she reflects, “felt like doing prison time.” She hated it all: the heat and the humidity; the scorpions and the snakes; the starving dogs and malnourished children. Not even their Hemingway-inspired pet names of “Squirrel” and “Bear-Bear” could fortify Fry and her husband against the stark realities of primeval jungle life. Their nascent marriage quickly strained.

By year’s end, however, Fry had experienced a change of heart, if not toward her husband, then toward the children she had come to love. With the help of her neighbors, she could produce a passable tor-tilla. More importantly, she could walk and live among them without passing judgment, accepting them for who they were and being accepted by them for who she had become. If they remained, in essence, an embryonic, undeveloped society, Fry had blossomed into a strong, independent, self-reliant young woman.

It’s this admirable metamorphosis that elevates acclaimed journalist (Time magazine, McSweeney’s, the Boston Globe) and short-story author Fry’s memoir-cum-travelogue into a poignant and revelatory coming-of-age story. Remember, the time was 1962. Back home in the States, safe within their ivory tower confines, Fry’s contemporaries were just beginning to flirt with the idea of feminism. Killing her own food, hacking at jungle growth with a machete to clear a path to the bush latrine, and molding young lives in a rugged classroom using only her wits as a guide, Fry was living those ideals in a way other women her age couldn’t begin to imagine.

But as it turns out, when you have imagination, cooking a tapir—or becoming your own person—isn’t so hard, after all.

Reviewed by

Carol Haggas

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.