Hunt for the Jews

Betrayal and Murder in German-Occupied Poland

In re-examining the myth of the “righteous,” Grabowski unearths disturbing truths about Polish citizens’ complicity in the Holocaust.

Jan Grabowski returns with an unflinching study of the Judenjagd, the post-ghetto “hunt for the Jews” in rural Poland. The book focuses on Dabrowa Tarnowska county, a bucolic region with a prewar population in the tens of thousands, including a well-integrated and sizable Jewish community.

Grabowski’s pages seek to upend equivocations surrounding neighbor involvement in the extermination of Europe’s Jewry. He adopts Dabrowa Tarnowska as a control case for examining the actual complicity of the Polish citizenry in the deaths of their Jewish neighbors.

Dabrowa Tarnowska’s Jews, Grabowski shows, were culturally entwined with their neighbors in a way which urban Jews often were not. Nevertheless, though Dabrowa Tarnowska citizens were incensed by the intrusion of German soldiers in their region, they exhibited a ready willingness to betray the Jewish neighbors they’d always lived alongside.

Grabowski’s fastidiously researched chapters make use of survivor testimonies, eyewitness accounts, and court transcripts to analyze the systematic isolation and extermination of Dabrowa’s Jewish community. The bulk of Grabowski’s project focuses on what came after the liquidation of Dabrowa’s ghettos, to the Jews who remained behind. Some sought shelter with former neighbors, or in self-constructed bunkers in buildings or in the Dulcza forest.

Those lucky enough to find hiding places with neighbors often found themselves quickly turned out when their “payments” ran out, or that they were sold out by others aware of their concealment. Those who subsisted in the forests of the county were often smoked out by self-appointed search committees, whereupon they, too, were promptly executed. All in all, Dabrowa Tarnowska’s Jewish community had an average survival rate of one or two in a hundred.

Grabowski carefully troubles the misconstruals and misnomers common in postwar explorations of the Holocaust, particularly the application of terms like “righteous” to any and all credited with even briefly helping Jews. He shows that, often, those who concealed Jews also exploited or betrayed them, even becoming their murderers. That their ranks are exaggerated and celebrated in contemporary Polish culture belies the depth of the citizenry’s often zealous collusion. Grabowski also re-examines the involvement of the local church, and of the Baudienst, the paramilitary youth organization whose place in Polish history is unsullied even by its documented involvement in Jewish liquidations.

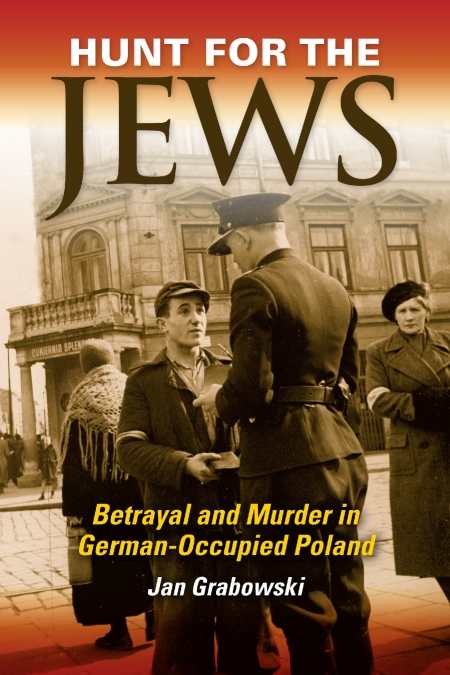

His accounts also laud the undercelebrated, ordinary citizens who concealed Jews for years, often with no reward and at great personal risk ever after. The firsthand accounts he makes use of, as well as the period photos included throughout, remind readers of the extent of the tragedies, and bring into new relief the particular horrors represented by years of sustained and encouraged exposures and betrayals.

Though thick with careful documentation, Grabowski’s project reminds readers of the humanity, ingenuity, and determination of both the survivors and the lost, all the while refusing to shirk from holding those complicit in their deaths morally accountable. This important, often disturbing, exploration of how genocides happen is on par with works from Hanna Arendt and Gitta Sereny and is enriched by the author’s clear compassion for those who were compromised or lost.

Reviewed by

Michelle Anne Schingler

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.