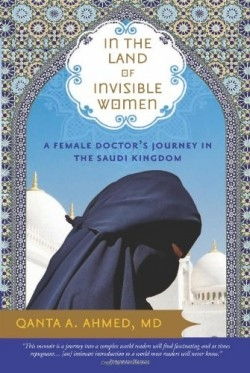

In the Land of Invisible Women

A Female Doctor's Journey in the Saudi Kingdom

Whether or not a reader is familiar with the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Dr. Qanta Ahmed’s debut memoir is a mesmerizing read. It’s also the perfect primer for those who want to know what life is really like for women in a rigidly orthodox Muslim country. A British citizen of Pakistani origin, Ahmed completed her medical training in internal medicine, pulmonary disease, and critical care in New York City. At the completion of a fellowship in sleep disorders, she found that her visa application to stay in the United States had been denied. Without much thought or familiarity with the Kingdom, Ahmed accepted a job offer to work at the King Fahad National Guard Hospital in Riyadh.

Although she had been raised Muslim, Ahmed had very little knowledge of the religion. Through her writing, readers gain an education as well. Further, Ahmed’s firsthand experiences in a Muslim country elucidate facets of its culture, from an explanation of blood money to the practices of polygamy. One of the most moving sections of the book covers Ahmed’s Hajj, or pilgrimage to Mecca, the holiest site for Muslims. It’s on this journey, ripe with adventures and side turns, that Ahmed discovers the importance of religion to her, and embraces all the positivism of Islam.

Yet, throughout, Ahmed encounters various dichotomies, especially because she is a Westernized Muslim woman. Right away, her experience wearing an abbayah—a robe that covers from head to toe except for the eyes, which all women in the Kingdom must wear when they go out in public, no matter their nationality or beliefs—was paradoxically restrictive and freeing: “As I fastened the abbayah in front of a mirror inside the makeshift dressing room, I watched my eradication. Soon I was completely submerged in black. No trace of my figure remained. My androgyny was complete.” She described it as a “strangely inviting prison” and “in some respects the abbayah was a powerful tool of women’s liberation from the clerical male misogyny.” Only through the abbayah’s protective layer can a woman get anything done.

There are other examples of the way Saudi women “benefit,” from their female status. In marriage, women receive a mahr from their new husbands, which is a substantial fortune. And if they divorce, the woman gets to keep all of her mahr. Divorce is also easily obtained; if a man wants to take on a second wife (in Saudi Arabia, he can have up to four), this alone is grounds enough for divorce. Yet, in a divorce, men are awarded custody of children over the age of seven or nine, a fact that runs counter to a Westerner’s way of thinking.

Polygamy is another intriguing topic discussed here—one of Ahmed’s colleagues divorced her husband for wanting to take on a second wife, then confessed that she herself would like to become a second wife: “I am going to marry a man who is already married. I don’t want to marry a naïve bachelor. I want to marry a man whose primary needs are already met.” Ahmed, the Westerner, found this logic puzzling, and rather sad.

To a degree, the divorcée’s story is an indicator of a Saudi view Ahmed encountered in a more global realm—that of anti-Semitism. Ahmed was in Riyadh during 9/11, and these chapters are some of the most moving, disturbing, and insightful of the book. Ahmed was saddened and distressed—she is, after all, extremely attached to New York and America—and taken aback by her colleagues’ excitement in reaction to the attacks. Female Saudi obstetricians in her hospital bought cake for their staff to celebrate. Her friends talked about how America “deserved” this tragedy because of its support of Israel. It’s a turning point for Ahmed, as she uncovers the complexity of allegiances. It’s also an affecting illustration of how unaware some Westerners—Ahmed included—were of the antipathy much of the Middle East harbors for the West. It points to ironies and paradoxes on so many levels; many of her Saudi colleagues had their medical training in the States with Jewish mentors, and benefit from oil money—yet they flatly “hate the Jews.” While such attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors disappointed and isolated Ahmed, they fit neatly into her growing understanding of the Kingdom.

Ahmed’s portrayal of Saudi Arabia during her two years there is one of both fondness and frustration, and a fascinating one at that.

Reviewed by

Olivia Boler

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.