Incoming

Collected Stories

Characters are relatable and fully human, and their actions resonate with the choices humans must make.

Vic Amato’s sixteen tales in his Incoming: Collected Stories are literary explorations of the corridors of the human psyche, some familiar, some dark, all incorporating empathetic portraits of people, including married couples, young men on the cusp of adulthood, and even a sympathetic examination of the quirky among us.

Nearly every piece is set in the modern age; the one exception is “Everyone Hates Malvolio,” a sardonic takeoff on Twelfth Night. That tale offers a wry allusion to Clintonian fiascoes when Malvolio observes, “Perhaps there are places where the meaning of the word ‘is’ is not debated.” One of the more affecting stories, perhaps based on the author’s own professional experience as a social worker, is the opening story, “Death by Peanut Butter.” A mentally ill man washes up in a shelter and dies after choking on a peanut butter sandwich that should have been cut into bite-size pieces, the neglect purely accidental. A parable for what happens among the least of us?

Amato’s deeper explorations of young males in America are “Dad List,” “Scarlet Amber,” “Second Person, Sixty-Seven,” and most powerfully “Camille.” Each features a protagonist floundering, pulled by love (or lust) or by the threat of the military draft. Each ring with veracity, and the conclusion of “Camille” is especially poignant. As elsewhere in the collection, there are contemplations of the road not taken, and “Camille,” among others, delves deeply into the swampy morass where the sea of love and passion washes up on the shore of hard reality.

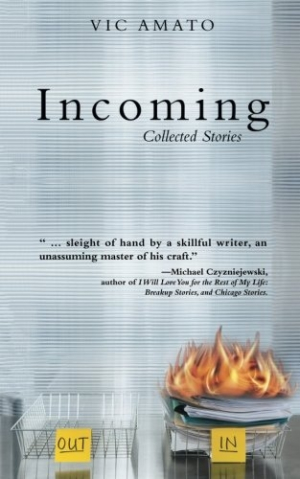

The title and cover (a desk with an in-box and out-box) seem ironic opposites considering how often the characters and plots reference the military, where “incoming” is a term for being targeted by enemy fire. The author’s writing is clean, clear, and concise. There’s no literary obtuseness. Whether the tales spin out in first or third person, or have the aura of a roman à clef, characters are relatable and fully human, and their actions resonate with the choices humans must make. Amato has the ability to frame the prosaic with meaning, and he generally refrains from postmodernist ambiguous endings.

Amato explores edgier topics in “Elevator Race” and “The Man Who Didn’t Care.” The first is a postracial study in racial stereotyping, fascinatingly accomplished as a good man attempts to convince himself he doesn’t see color. The other, perhaps, could be a Swift-esque “let them eat the babies” examination of capital punishment.

Most of the stories are set in the northern Midwest, Michigan in particular, although, coincidence or not, two stories incorporating violence play out in Cozumel and San Francisco. It’s only in those stories that settings become “character” where in other stories settings often fade into the background.

Fans of short fiction will enjoy more than one piece in Amato’s eclectic collection.

Reviewed by

Gary Presley

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.