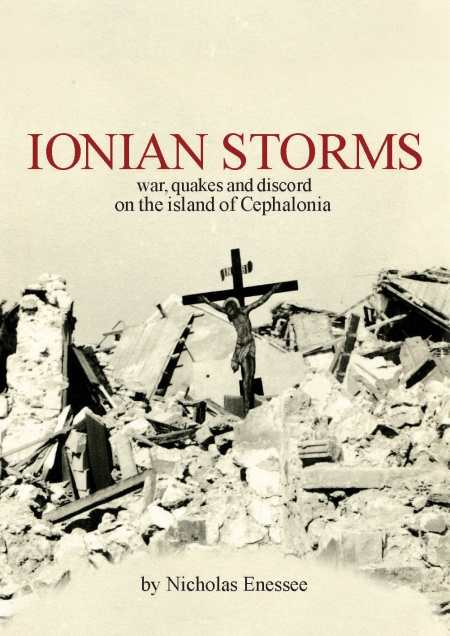

Ionian Storms

War, Quakes and Discord on the Island of Cephalonia

For those whose only knowledge of the Greek island of Cephalonia comes from watching Captain Corelli’s Mandolin, the homogenized film version of Louis De Bernieres’s 1995 novel Corelli’s Mandolin, Nicholas Enessee’s new book Ionian Storms: War, Quakes and Discord on the Island of Cephalonia promises to be an eye opener. Enessee neither shies away from nor celebrates the very issues that many found controversial in the film and novel about the fictional Corelli. Enessee’s nonfiction narrative gives an account of a particularly devastating period in Cephalonian history and also includes excerpts from the diary of a woman named Helen, whose life story is entwined with that of the island. Together, those histories form a well-rounded tale of a time of severe hardship in Cephalonia.

Although Enessee provides relevant background information about earlier days, he concentrates here on the period from just before World War II through the 1950s, years of immense turmoil on the island. One of the seven main Ionian Islands off the west coast of Greece, Cephalonia was taken over by the Italian army in 1941, when Axis forces occupied Greece. Later, in 1943, Germany seized the island from the Italians. Meanwhile, the Cephalonians, a proud and independent people, struggled under enemy rule and found themselves exposed “to all kinds of extreme situations: suffering, cruelty, arrogance and stupidity.”

Enessee stresses the strength and resilience of the island’s native population as the people rally against occupation, and he does not hide or minimize their bitterness. He includes significant and striking detail, and the story he tells is both revelatory and noteworthy. As he discusses the rise of the Communist party in Greece—which is directly tied to foreign occupation—and how it takes its own toll, he clearly shows the consequences of the Greek Civil War and its further destruction of the island. When he writes of the devastating earthquake of 1953, he makes it easy to wonder why anyone left on the island did not simply give up and leave. In Helen, a well-educated Londoner of Greek extraction who married a Greek man and moved to Cephalonia, Enessee succeeds in presenting both a balance and a foil to his historical account. She serves as both an outsider and an insider in the telling of his story, and without her perspective the tale would be less balanced.

What Enessee has to say in Ionian Storms is both informative and important. His book includes a Greek perspective that Americans who have based their information about Cephalonia on films and novels may have missed. Ionian Storms is an intense, gripping story. Unfortunately, the text is flawed by typographical errors, misspellings, dropped words, and nonparallel sentence structure. With proper editing, Enessee’s would surely appeal to historians, World War II enthusiasts, and discriminating fans of historical nonfiction.

Reviewed by

Cheryl Hibbard

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.