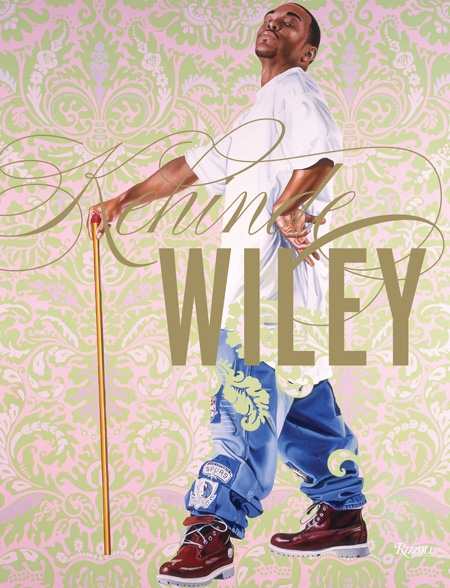

Kehinde Wiley

As with most great art, Kehinde Wiley’s portraits reflect the time and place in which they were created: in this case, current-day cities. They also comment on the history of portraiture, specifically upending traditional European representations of power and beauty. The paintings are distinguished not only by their subjects—young black men cloaked in hip-hop couture—and the technical gifts of their creator, which are considerable, but in their tremendous (and somewhat humorous) appeal.

Raised in South Central Los Angeles by a single mother who is an academic, and trained at the San Francisco Art Institute and Yale’s School of Art, Wiley, now thirty-five, has continually mined semiotics and poststructuralist theory for ways to engender the messages he conveys in his work—namely, that marginalizing black as the absence of white is no more credible in color theory than it is in cultural theory.

As artist-in-residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem, Wiley hired young men off 125th street to pose for the photographic studies that served as precursors to his painted portraits. They were invited to choose the pose they’d like to assume (a process that’s been compared to “vogueing” by critics who contributed essays to the book), primarily from Renaissance and Baroque art history books, and were represented wearing their own clothes.

Treating the material surfaces depicted in his work—down jackets and plaid boxers—with the same attentiveness to detail by which the British and Flemish masters rendered the ermine capes and velvets of their noblemen subjects, Wiley’s hypersensual, homoerotically charged images are provocative to the extreme. The viewer is invited to closely inspect people for whom staying in motion on the street has become an art form in itself; but for all the bravado of his young sitters, it’s their vulnerability that continues to resonate when viewers turn away from the portraits.

Perhaps this quality is a function of the “ongoing surveillance” and “incarcerating limits” inherent in portraiture, as discussed by the critics who’ve prepared a great foundation for understanding Wiley’s efforts in this most handsome volume. Or, perhaps it’s the artist’s style of wallpapering the backgrounds of his canvases with gardens of two-dimensional flowers that casually bleed into the foreground, domesticating his tough subjects in a sweet embrace. Either way, Wiley’s employment of the languages of light and of power, of race and of the body communicate a reverence for his subjects that transcends time and place to leave us astonished.

Reviewed by

Julie Eakin

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.