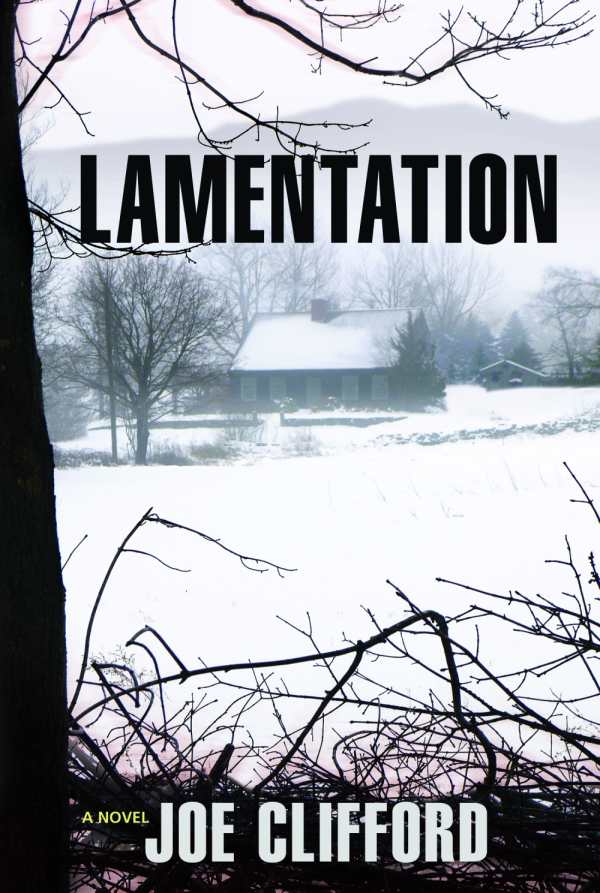

Lamentation

Cliffhangers and a small town that “rings true” propel this literary crime thriller.

In order to ring true, novels set in small towns should capture something of the local citizenry’s provincial mindset, that sense of “us vs. them,” and in this respect, Joe Clifford’s novel Lamentation succeeds admirably. Set in Ashton, New Hampshire, the novel evokes a world of diners, gas stations, county jails, run-down farmhouses, and motor inns—a mountain town inhabited by Jay Porter, a young man who ekes out a paltry living salvaging junk:

“A dumpster sat in the snow-covered driveway overflowing with waterlogged pads of fiberglass, chunks of splintered wood, jagged shards of glass, trash bags jam-packed with leftovers that didn’t quite translate into dollars and cents.”

Jay’s difficult, hand-to-mouth existence—which includes a strained relationship with his ex-girlfriend, Jenny, and their young son, Aiden—is further complicated by the misadventures of his older brother, Chris. A longtime, unapologetic drug abuser, Chris drops in and out of Jay’s life and by his presence almost always makes things worse.

Clifford’s introduction of this unsavory individual demonstrates his skill at painting a character with effective brush strokes: “He wore the same threadbare T-shirt he always did, dark blue with a pair of faded cherries, from the old Pac-Man arcade game. Every time I saw him he was wearing it. What kind of life do you lead where you only own one T-shirt?”

After Jay bails Chris out of the local holding cell, his errant brother’s “business partner” (a business purported to revolve around computer salvage) is found murdered—and Chris is a prime suspect. The story of Lamentation, while more than a mere mystery, focuses largely on Jay’s efforts to find his brother before the authorities do, and to expose a deeper, ugly truth hidden in a missing computer hard drive.

After a slow start that relies a bit too heavily on Jay’s memories to anchor the narrative, Lamentation kicks into gear and moves briskly. Clifford is particularly adept at the use of chapter-ending cliffhangers. Although some of the twists and turns feel underdeveloped—and the same might be said for some of the secondary characters, including Jenny—there’s no arguing with the novel’s propulsive forward movement and satisfying conclusion.

Clifford, a former self-proclaimed “homeless junkie,” brings authority to his description of drug addicts and biker gangs, while maintaining the perspective of small-town America: “It’s funny, when you spend your whole life in a small town, people who don’t belong stand out like ten-foot aliens belting show tunes.”

Reviewed by

Lee Polevoi

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.