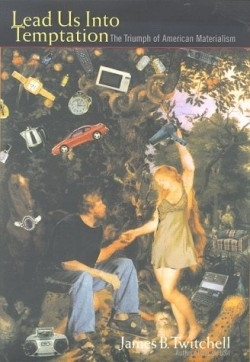

Lead Us Into Temptation

The Triumph of American Materialism

If hunger has no ambition, why do we still buy so many things once our basic needs are fulfilled? According to Twitchell, culture critic and author of Lead Us Into Temptation, it is the “getting and spending” we crave, thereby turning temptation into a consumer demand. It is Twitchell’s belief that people do not want things as much as they want meaning, and in today’s consumer society, meaning resides in manufactured objects.

Twitchell offers a provocative, if narrow, theory explaining the commercialism that drives our society. Disputing the myth of the consumer

as the “dumb ox” and the producer as the “scheming farmer,” he advances the idea that it is really consumers who hold the power in the marketplace, determining which goods best serve as self-reflecting mirrors. “Don’t like who you are? Buy different brands” is the modus operandi in a culture where selfhood is registered by material things.

To prove that it is not the goods but instead the consumer’s image that is being packaged and sold, Twitchell devotes chapters to advertising (the “lingua franca of commercial culture”), packaging (“the Venus Flytrap for humans”) and branding (designer names are “magical dust” sprinkled on products). Posited, too, is the idea that commercial culture has continued the role once played by religion since “both sell peace of mind,” only now it’s Wonder Bread and Coca-Cola instead of the wafer and wine.

Although thought-provoking, Twitchell weakens his argument by dismissing critical theories that explore the influence of advertising on

unwary consumers (even in his list of references at the end). Also, contrary to Twitchell’s view, not every American finds the Man from Glad to be an adequate substitute for the Man from Galilee. The book offers no proof that there is indeed a “willing conspiracy on both sides of commercial transactions” to be enchanted in this way, nor that “melancholy angst” can best be kept at bay by a trip to the mall.

Twitchell is an uneven stylist and is at his best in his literary allusions (Wordsworth’s “getting and spending”) and in his way with a turn of phrase (“Snake oil to the cynic is often holy water to the eager”). Within the confines of his narrow theory, he attempts to assess the good and bad of consumerism, conceding its vulgarity, but praising its populism.

Reviewed by

Judy Hopkins

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.