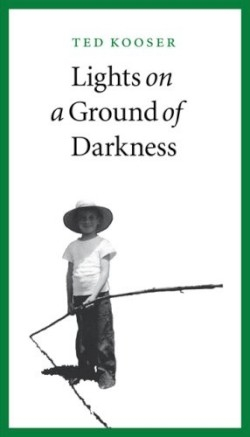

Lights on a Ground of Darkness

Poet Ted Kooser’s refreshingly compact meditation on his youth in Eastern Iowa is an essential addition to the growing number of prose autobiographical works by established Midwestern poets (see Mary Swander’s The Desert Pilgrim and Debra Marquart’s The Horizontal World: Growing Up in the Middle of Nowhere). Kooser is nothing if not established, with several award-winning books among the twelve volumes of poetry he has published—most recently, Valentines—and his recent position as U.S. Poet Laureate 2004-2006.

Kooser swoops into the landscape of the East bank of the Mississippi, in Northern Iowa, painting a picture of Guttenberg, a town that barely supported whatever slight trade took place many generations ago. Gradually, readers meet the large extended family that Kooser knew as a boy. All of these figures are gently rendered; one of the central, recurring figures is his Uncle Elvy, who suffered from cerebral palsy, but was dearly loved and more than adequately cared for by Kooser’s grandparents and other family members.

Kooser’s narrative does require more than casual attention. The poet in him can’t resist experimentation, however slight, in the sense of jump-cuts to different points in his family’s history, and sometimes these can catch the reader by surprise. What remains constant throughout the book, however, is a sense of the love that his family had for each other, and lack of concern over their economic hardships. Kooser never lets the reader forget that he’s telling the story, and ultimately the book becomes a meditation on his own life and relationship to his parents. From a light, episodic, and uplifting series of vignettes that carry the reader through the first two-thirds of the book, Kooser leads us to the sobering ends of the lives of his grandfather, Uncle Elvy, his father, and finally his mother, for whom (Kooser states in the preface) he was driven to finish the book.

Readers looking for a vivid description of the landscape and human condition in the early twentieth-century Midwest will be satisfied, as will readers looking for a metaphysical meditation on the nature of our perception of time and what survives in our memories. Irises are a recurring motif throughout Kooser’s narrative, with iris roots being passed from generation to generation in his family, relocating and blooming anew with each new recipient. A fitting play on words, perhaps, since the iris is also what regulates the amount of light entering the eye. Kooser’s book is a gift—his irises are open wide, and his book will open those of his readers, to fully appreciate the fragility of life and a family’s love.

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.