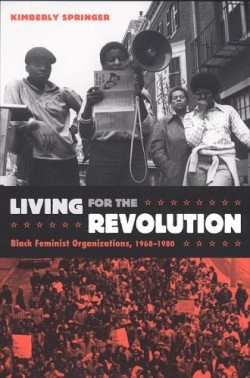

Living for the Revolution

Black Feminist Organizations 1968-1980

Black feminist organizations are an appropriate place to begin chronicling the history of African American women’s social clubs. Though clubs have been in existence since the nineteenth century, the author focuses her study on five contemporary black feminist organizations, all of which were organized by 1968 and defunct by 1980: the National Black Feminist Organization, the Combahee River Collective, the Third World Women’s Alliance, Black Women Organized for Action, and the National Alliance of Black Feminists.

Springer, who is also editor of Still Lifting, Still Climbing: African American Women’s Contemporary Activism, has written numerous articles about black feminism for anthologies and journals and is a lecturer in American Studies at Kings College, University of London.

For quite some time, black women have been in a precarious position regarding the politics that are of interest to them. Active in civil rights organizations, they have been asked to ignore sexism and other gender-related concerns in order to focus fully on the race question. These established organizations allowed few opportunities for black women to assume leadership roles or to nourish their attempts at activism. Some black women, though skeptical, turned to white feminist organizations, but quickly learned that mainstream feminism was not eager to take on the concerns of women of color. At the core of black feminism is the idea that black women are multiply oppressed by race, gender, and in some cases class and sexuality.

Interested in both civil rights and feminism, black women formed their own organizations determined to do the work that mattered to them. The five organizations studied took an anti-racist and anti-imperialist stance and confronted sexism, heterosexism, and other forms of discrimination in the United States and in Third World countries. They challenged racial and sexual stereotypes of black women (and men and children) in the media, low-wage domestic positions for black females (including some college graduates), unequal pay, forced sterilization, and general health-care issues.

Using interviews with key figures like Francis Beal and Barbara Smith, and organizational documents such as newsletters, files, and calendars, Springer describes how and why these organizations were started, including their objectives, accomplishments, and demises. Maintaining these organizations beyond twelve years proved difficult. Black feminists learned that black women are not monolithic. They too hold a variety of ideas about class, educational attainment, sexuality, and other topics. Internal “challenges” related to differences in ideology, difficulty securing adequate funding, and unequal distribution of responsibilities contributed to the demise of the organizations.

Though it often reads like a doctoral dissertation and is a bit repetitive throughout the six chapters, Living for the Revolution proves that these organizations have left comprehensive maps, which black feminists can make use of today and in the future. Who knows? Despite the different ways that black feminism(s) are practiced, there could be new contemporary black feminist organizations in the works.

Reviewed by

Kaavonia Hinton

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.