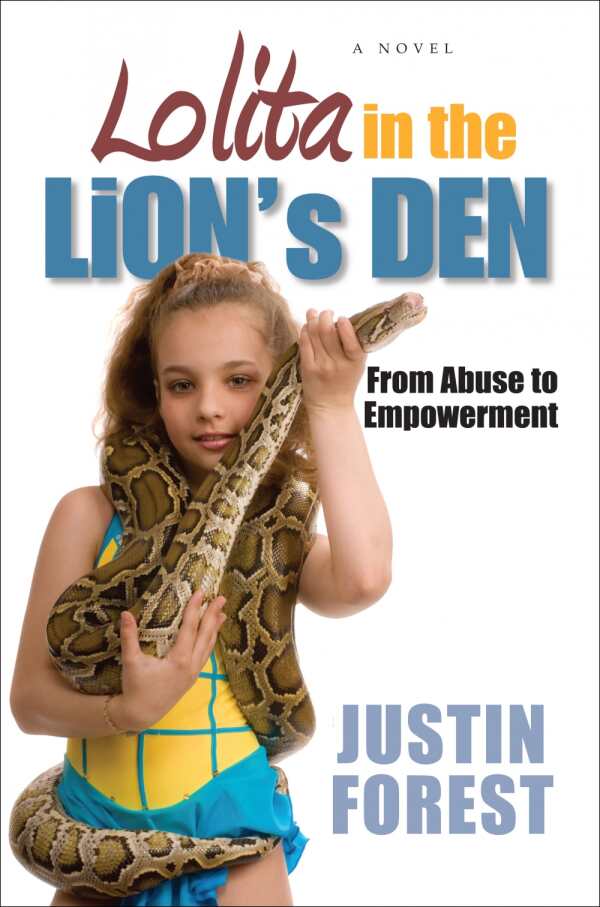

Lolita in the Lion's Den

From Abuse to Empowerment

A character ashamed of his disturbing desires illuminates important questions about society’s sexualization of young girls.

Lolita in the Lion’s Den, the debut novel from literature professor and sexuality researcher Justin Forest, is the provocative exploration of meeting points between empathy and declared perversions. Through his protagonist, Glen, Forest questions the costs and benefits of current attitudes toward children and sexuality, with piquing, if often disturbing, results.

The novel is written in confessional form, with Glen recounting dark, formative moments from his childhood, and juxtaposing these to the challenges faced by those whose adult sexualities don’t mesh with desired norms. The interplay is an important and psychologically effective technique, rendering Glen relatable, if not always appealingly so.

The impetus for this exploration seems to coincide with the birth of Glen’s children, whose innocence forces him to confront his predilections more openly. “I have a Lolita Complex,” he tells his wife. Really, his admission ties to feelings of stimulation connected to young girls. He never acts on these interests, but associated guilt and fear have plagued him his whole life.

Repeatedly, Glen ties his guilt, as well as his absolute respect for consent, to the trauma of surviving a sexually abusive father and to feelings of failure related to the sister whom he could not save. Glen, the reader learns, is the wannabe hero who never was. The novel volleys between condemnations of those who do offend, reflections on what it’s like to live with attraction toward girls too young to consent, and long diatribes against contemporary approaches to the sexualization of children, particularly girls.

Glen is both a thoughtful and a frustrating narrator. His struggles to understand his own leanings become an engaging battle of dueling wills, and his white-horse aspirations will earn equal measures of admiration and annoyance. “You keep talking about how you want to help [women],” his therapist tells him at one point, “but you seem to talk a lot about YOU.”

This incisive declaration looms over the novel’s chapters, in which passionate Glen sometimes veers into illogical territory, projecting his fears or misgivings onto imagined government agents, even deleting pictures of his newborns out of the conviction that their nakedness will be seen as pornographic. Self-loathing leads to pugnaciousness. Forest is successful at making his character heard, if not likable.

That Glen is given to taking his caution too far does bring many of the novel’s inquiries into better relief. Readers will find themselves asking questions with Glen: How far is too far? How do we empower young people to embrace their sexuality while outright condemning the mention of their sexualization? Some of Glen’s conclusions are troublesome, and some of his statistical and legal claims are in dire need of footnoting, but the questions themselves remain important and worth engaging.

Glen picks fights with plenty of potential readers—with law enforcement, with feminists, with academia—yet the issues he raises are significant enough to justify their participation in connected conversations. Lolita in the Lion’s Den is a disturbing, revealing, and unflinching account of taboo sexual impulses, and well worth reflective consideration.

Reviewed by

Michelle Anne Schingler

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.