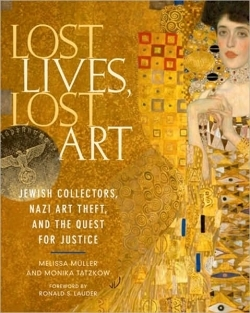

Lost Lives, Lost Art

Jewish Collectors, Nazi Art Theft, and the Quest for Justice

Lost Lives, Lost Art is a collection of a dozen or so stories of the most despicable acts of betrayal, theft, conspiracy, and murder in modern history. And though labeled “history,” these are stories as fresh as yesterday’s New York Times—stories that, for the most part, remain unresolved.

The Nazi confiscation of tens of thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands, of pieces of art from German Jews, is called by one art expert “the most tragic chapter in the history of plunder.” The book is meticulously researched, brilliantly and dispassionately written, and is in all likelihood a game changer in the world of art, art provenance, and art restitution that will resound for years to come. The seventy-five color and 125 black and white images show a fraction of the lost treasure.

The stories are told one collector at a time, one agonizing and bewildering loss at a time, of the “degenerate” art that Hitler openly despised and secretly coveted. Lilly Cassirer, desperate to get out of Germany, sold Pissarro’s Rue Saint-Honoré to her “friend” Jakob Scheidwimmer for 900 Reich marks (about $1,000). That same painting now hangs in a museum in Madrid and is insured for €5 million, which is still probably only a tenth of its value. The famous art dealer Walter Westfield, who was unable to buy himself out of Germany, died at Dachau. Among the “degenerate” artists whose works were swept away were Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Piet Mondrian, and Egon Schiele. Klee’s seminal Swamp Legend was stolen by Hildebrand Gurlitt, Hitler’s official buyer for the Führer museum in Linz. Just to make it all legal, he “bought” the painting in 1941 for 500 Swiss francs.

Lost Lives, Lost Art simply could not have been written before now. It took the reunification of Germany and the fall of the Soviet Union to allow experts like Melissa Müller and Monika Tatzkow to begin their research in earnest. Finally in 1998, forty-four countries, including the United States, reached agreement on what is now known as the Washington Principles to attempt to restore the looted art to the heirs of the original owners. But the authors tell us that the path to recovery has been anything but smooth, and many countries such as Hungary and Spain have not signed the principles.

Müller is the author of Anne Frank: The Biography, and her sections of the book read like literature. Tatzkow is a leading authority on the recovery of stolen art, and her sections read more like summations to a jury, which is where they will likely wind up. Together they have written a beautifully illustrated chronicle of the worst time in human history.

Reviewed by

Jack Shakely

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.