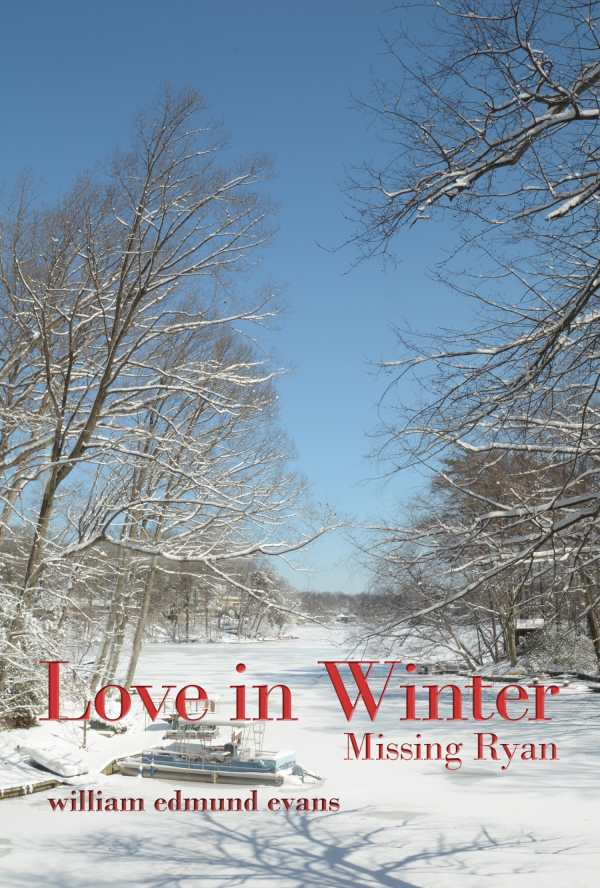

Love in Winter

Missing Ryan

Love in Winter reaches for the art of poetry to clothe a father’s naked grief.

William Edmund Evans’s Love in Winter: Missing Ryan collects poems written in the long season of grief. As its speaker navigates the first winter after his son’s suicide, winter proves to be more than just a few months’ passage: it becomes a season of the soul.

Divided into five sections, these sixty poems are occasionally endmarked with the season and year of their composition. The implied chronology is linear. While time may be experienced linearly, grief and memory aren’t, so this organization fights against the narrative impulse of the poems’ wider arc. Assembling a story from the raw, often abstract emotions and contexts of the volume requires a significant amount of work off of the page.

High on dissonance and with occasional narrative gestures, these poems are an assemblage of emotions, experiences, memories, and images that imply rather than state their purposes. “Snows of a Dream” stands as the volume’s ars poetica, stating,

Still

it could be possible

winter yet may cauterize

the bleeding out

least offer

flash freeze images

parsed to clean abstraction

staring toward the north

launched south

now closing in, a shirtless man

false courage his pale strategy

taunts a beggar trying art.

There’s a sprawling range to the selected poems that exhibits the tension between the title’s two elements. “Love in Winter” and “Missing Ryan” are both powerful engines, and their union opens up a broad space for exploration. Winter, birds, and nature; religion, art, and fate; and rituals, history, and tragedy are frequent themes. The poems themselves range from intensely personal and almost spare reflections to long narratives that explore the interconnection between the speaker’s personal history and outside events.

Often, the connections the speaker finds between his personal grief and the larger world are surprising. In poems like “Ghost from Eden,” parental grief offers him a point of intercession into Middle Eastern domestic terrorism while also illustrating grief’s demanding, avaricious self-absorption. But the sheer scope of the book’s topical influences—which makes several of the poems individually interesting—doesn’t add up to a whole volume that’s greater than the sum of its parts.

There’s an open-endedness to many of the poems. The shorter poems are the least affected, their brevity lending itself to easier intuitive leaps between the content and its implications. What happens in the leap is often beautiful, as in “I Know the Moon,” which opens with “I know the moon by science” and closes with “I know by science you are gone.” The poem’s imagery and language carry a vast, unspoken freight.

In longer poems, the impulse toward implication with scant explication is given free play without equal attention given to language’s power, merit, and weight. Several poems address racism, but a lack of context and relevant details makes their messages and intentions unclear, particularly when racially charged language is used. The results are lackluster, and longer poems’ attenuation enervates their ability to deliver the same lightning shock of distillation.

In “Compelled to Witness,” the speaker states, “Art’s a poor man’s sable / a father’s threadbare comfort.” Love in Winter reaches for art to clothe a father’s naked grief, grasping onto whatever impulse is offered, no matter how raw or disparate it seems, no matter how far afield it takes him.

Reviewed by

Letitia Montgomery-Rodgers

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.