Making War at Fort Hood

Life and Uncertainty in a Military Community

As seen through the author’s eyes, war distorts and reconfigures everything it touches—bodies, minds, values, fraternal and romantic relationships, local and national economies, and, indeed, the entire context of life. None can stand apart from this reality. The greater war’s absurdities, the harder those involved must strive to make sense of it. Supported by a research grant, MacLeish lived near Fort Hood, Texas, in 2007 and 2008, when US forces were still fighting in Iraq. He spent much of this time talking and “hanging out” with soldiers who had returned from the war with varying degrees of physical and psychic damages. He does not appear to have spoken with officers or others on this dusty, 150,000-acre base with a vested interest in putting the best face on war.

It doesn’t take long for the author to encounter war’s infuriating contradictions: better armor that saves soldiers’ lives only to facilitate them being put at risk again and again; soldiers with traumatic brain injuries who, despite having extensive support systems, dare not use them fully for fear of losing or diminishing their veterans’ benefits; a military that spends billions to build strong “families” within the service while simultaneously shattering actual ones through multiple deployments.

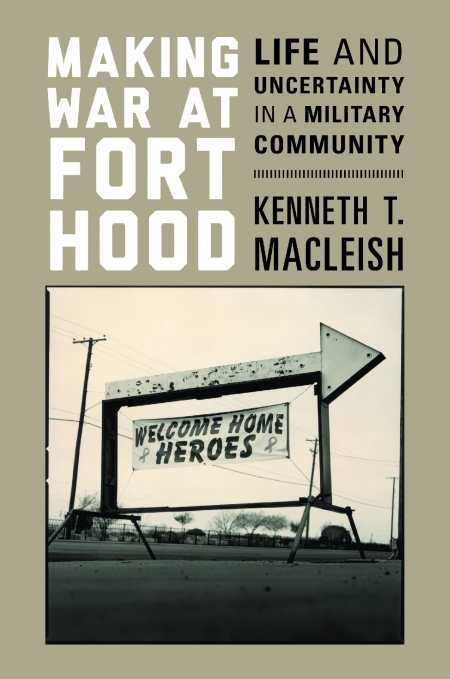

Then there is the “burden of gratitude” returning soldiers have to deal with—the drip, drip, drip of civilian thank yous in all their many and intrusive forms. Welcome and appreciated at first, these gestures—whether heartfelt or guilt-induced—eventually throb like an aching tooth. Says MacLeish, “soldiers confront a range of expressions of gratitude that they often don’t know what to do with: the fetishization of the soldier in public culture, the volunteers who greet planeloads of returning soldiers with waving flags and baked goods, and the individual forms of thanks that people in uniform encounter while going about their business out in the civilian world.” One of the most bizarre sections of this book is MacLeish’s description of soldiers being rounded up to sit in the broiling sun at a barbecue and listen to their praises being sung by a succession of people who know little or nothing of war.

MacLeish doesn’t debate the pros and cons of war—although both are implicit. The real thrust of his book is to show the American public—insulated from having to care greatly by an all-volunteer army and battles being fought on credit—that it nonetheless bears responsibility for the violence being done abroad and at home in its name.

Reviewed by

Edward Morris

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.