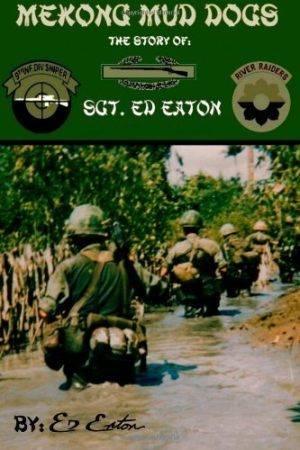

Mekong Mud Dogs

The Story of: Sgt. Ed Eaton

Eaton captures the danger, emotions, and political landscapes of the Vietnam War in this extraordinary story of heroism.

No one exemplified the utter danger and downright dirty work of the Vietnam War more than the combat infantryman. Ed Eaton lived his own remarkable combat role, and in his memoir, Mekong Mud Dogs, he tells it the way it was. Eaton’s attention to detail and the compelling nature of his war story do not disappoint.

Admittedly “not a writer by education or employ,” Eaton is nevertheless a natural storyteller, and he pulls no punches in rendering his almost daily brushes with death in the paddies and groves of the Mekong River Delta in the late 1960s, where units of the US Army’s Ninth Infantry Division were placed in different points of contact with Vietcong units. He chronicles his experiences as a radio operator, grenadier, and point man (“human mine detector”), followed by leadership roles in his squad and platoon. “My men,” Eaton writes, “were more important to me than any fucking bullshit rules of politicians.”

Eaton tells the story (also documented on the History Channel and the National Rifle Association’s Life of Duty Channel) of his extraordinary heroics on April 3, 1969: After a night raid, Eaton’s chopper was shot down. Severely injured, he fired on advancing VC troops from atop the downed chopper, changing weapons often. He thwarted the attack until backup arrived. Eaton was awarded several Purple Hearts and has also been recommended for the Medal of Honor.

Toward the end of his Vietnam service, hearing that combat units were being withdrawn, Eaton sensed that the United States was reneging on its support for the people for whom his fellow soldiers had died. Here he reflects on the Apollo 11 moon landing of that same summer: “Americans were looking at the moon. It was taking their minds off Vietnam and our struggles. We were now on the back burner. We already felt so alone and left to die by our country anyhow, and now here was a way for people to further put us and the Vietnam War out of their minds.”

This is one of several instances where Eaton remarks that he did not expect to survive the war. His prose, as in the above excerpt, is inelegant but efficient, and his writing style and mechanics (other than a few typos and unnecessary apostrophes) never inhibit the story’s impact.

That said, the memoir would benefit from more self-revelatory commentary. The fatalistic bravado that Eaton adopts in 1969 contrasts with the more insightful musings he has today. For example, like many of his fellow grunts, he consistently refers to REMFs (a derogatory term for rear-echelon troops) with undisguised contempt. But in the final chapter, Eaton recalls his 1994 return to Vietnam (“this would begin my healing”) and later remarks, “I would, in time…lose my hatred for REMFs by realizing their contributions.”

The book suffers from having been written over a period of many years and from an evolving perspective. Some of Eaton’s most important personal insights come only as a postscript to his narrative. Eaton could achieve a unity of purpose, and perhaps attract a wider readership, by updating this memoir to incorporate the scars and the healing from the point of view of the survivor he is today.

Reviewed by

Joe Taylor

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.