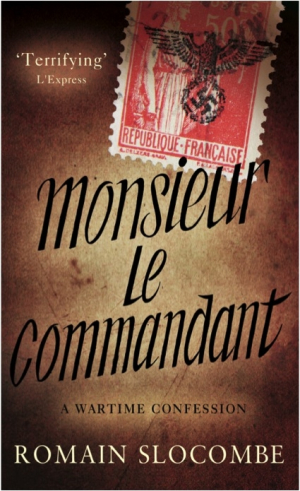

Monsieur le Commandant

The author reveals the deepest levels of morally backwards Paul-Jean’s depravity in uncompromising detail.

This excellent historical novel by Romain Slocombe chronicles the deplorable behavior of a privileged French author during the German occupation of World War II. Extensive research into this tumultuous period of the author’s homeland informs Monsieur le Commandant: A Wartime Confession. Written originally in French and nominated for the Prix Goncourt, a translation by Jesse Browner brings the story of Paul-Jean Husson to English readers.

Convinced that the liberal French government has undermined the moral values of his country, World War I hero Paul-Jean embraces the false promises of Adolph Hitler and pledges support for Maréchal Pétain’s puppet French government. Foolishly smitten with Ilse, his son Olivier’s personable wife, Paul-Jean devotes himself to protecting her. Even after a private detective confirms his suspicions about Ilse’s hidden German heritage, he continues to shield and covet her. Meanwhile, the French Gestapo increases its efforts to capture and punish French resistance fighters and undeclared Jews.

Written in epistolary form, Paul-Jean addresses a long letter to the German officer, or commandant, who controls the rural area of Normandy where he lives. Slocombe divides the letter into twenty-five chapters, ending with explanatory documents and notes. Told entirely from Paul-Jean’s perspective, with minimal dialogue, the narrative expertly enlivens the diverse characters and dramatic scenes they inhabit.

The book describes the invasion of France by the German army, forcing panicked French civilians into a massive retreat to the south. Parisian life, for the wealthy and well connected, appears to adjust seamlessly, as they enjoy their accustomed social and cultural events, obligingly shared with German officers. Slocombe shows Paul-Jean’s conflicted nature as he incites fellow townspeople to report a harmless Jew in their community to authorities but later reacts in horror when forced to witness the torturous deaths of French resistors captured by Gestapo thugs.

The characters of Ilse, Olivier, and resistors serve as moral counterbalance to Paul-Jean and other collaborators. When Isle tells Paul-Jean of her distress after witnessing a young student shamed for wearing the gold star that brands her as Jewish, he asserts that the girl will be safer when sent to a camp for Jews. Paul-Jean writes, “I could feel what she is feeling. I could put myself in her shoes.” Yet his subsequent actions render that empathy false.

Such a character cannot be admired, but Slocombe’s exceptional portrayal of Paul-Jean’s internal being succeeds in arousing pity for him. Deluded by belief in Catholic sin and guilt, the vanished life of old France, misguided patriotism, and romantic idealism, he lacks sufficient self-perception to understand himself or the true meaning of love.

Reviewed by

Margaret Cullison

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.