Murdering the Mom

A Memoir

There are some memoirs that seem so artful in the dissection of the joys and horrors of a life that they resonate long after that last page. Duff Brenna provides just such a story.

In telling the tale of his childhood, and especially his relationship with his mother, Brenna offers a sometimes-hypnotic, sometimes-electric glimpse into a boyhood fraught with uncertainty. With a distinctive, novelistic style (honed by writing six novels, including The Book of Mamie), he creates a work that’s suspenseful and unsettling, while drawing a reader in deeper through occasional use of the second-person perspective and present-tense language.

At times, the author seems to float on stream-of-consciousness recollection, disconnected to the events he’s just described. All of these subtle techniques combine remarkably well, creating a feeling of immediacy and connection; even those who’ve had relatively happy childhoods will be able to relate to the way that memory can play with a sense of time and place. For Brenna, he’s not just relating a story, he’s re-living it in the telling, and the ability to convey that process is one of the book’s greatest strengths.

Also compelling is the fact that he has plenty to re-live. Brenna recounts bullying and abuse at the hands of his stepfather, Nick Pappas, as well as sweet memories of a first love, and a description of the complicated relationship with his sister, a fellow survivor in their dysfunctional home.

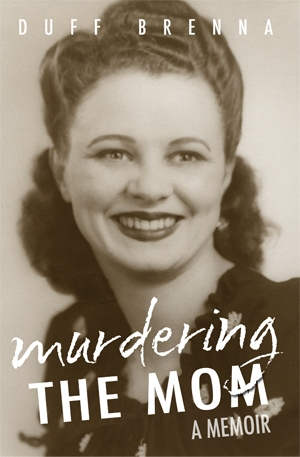

Central to it all is his mother, Janice Miles. By calling her “the mom,” Brenna establishes his mother as an entity who seems larger than life, a dominant figure who will never be completely knowable. That title fits well for Miles, an extremely charismatic firecracker of a woman who married six times and was once dubbed “The Black Widow” by friends for her ability to outlive her husbands. Brenna’s title is a nod toward their difficult relationship, and one particular fight in which Miles asks her son if he wants to murder her. While he replied that he didn’t, there was a part of him that wanted an end to the connection they shared, a way to cleave mother from son with the kind of finality that only death could bring.

“She said we had no idea what life had done to her, no idea what it was like to live with so much abuse and black depressions,” he writes. “So when she told me she wanted to die, I wasn’t all that upset. Maybe I was seeing a way out for myself. No more being her daddy, her caregiver, her decision-maker.”

When Miles did finally die, just before her seventy-fifth birthday, Brenna is more contemplative than angry. By then, he’d learned to see the humanity behind the cruelty of people like Pappas and Miles. But still, like many people recalling wrenching childhoods, his emotions surged with ferocity and he was left to ponder the truly momentous questions of life and, especially, of love. He writes “[B]ut love changes—it evolves, the purity of it becoming perverse mixtures of love and adoration, hatred and jealousy, tenderness, passion, devotion, loathing. What was left of those tumultuous emotions? I couldn’t sort it out. I still can’t sort it out.”

Even with this admission, though, Brenna provides a compelling attempt to untangle the emotional threads of his childhood. By viewing his past with such a sense of honesty and compassion, he delivers a memoir that’s a truly striking accomplishment.

Reviewed by

Elizabeth Millard

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.